This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is the work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

One of the economic selling points for mergers and acquisitions is that the new companies will be more productive. But as new research shows for the manufacturing industry, the result more often is not greater productivity, but higher prices.

Most models of the macroeconomy assume that individuals and businesses are perfectly rational. A new paper looks at how our understanding of macroeconomic policy would change in a world where people aren’t perfectly rational.

Monopsony is not a word that rolls off the tongue, but it’s increasingly a term that anyone paying attention to the U.S. labor market should understand. A new Council of Economic Advisers brief takes a look at the role of monopsony.

Links from around the web

Columnist Martin Sandbu riffs off a recent speech by Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen to note the return of Keynesian thinking that calls for more active management of aggregate demand through fiscal and monetary means. [ft]

The White House recently called on state governments to rein in non-compete agreements. Evan Starr of the University of Maryland who’s done research on the effects of non-competes writes on why they’ve become such a policy concern. [vox]

Inflation seems to be picking up in the United States and in other advanced economies. Should this increase be a concern? The only thing to fear, The Economist’s Ryan Avent argues, is that the Federal Reserve and other central banks won’t let inflation run stronger. [free exchange]

Advance data for gross domestic product for the third quarter of this year came out this morning. While they showed an uptick in growth, the pace of growth in recent years has been quite lackluster. Why? Alana Semuels runs through some of the theories. [the atlantic]

Before the Great Recession, some economists, led by former Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke, were concerned about a global savings glut emanating from East Asia. The savings rate of East Asian economies contributing to the glut back then was about 35 percent of collective GDP. Now it’s 40 percent. The Council of Foreign Relation’s Brad Setser lays out the data on Asia’s persistent savings glut. [follow the money]

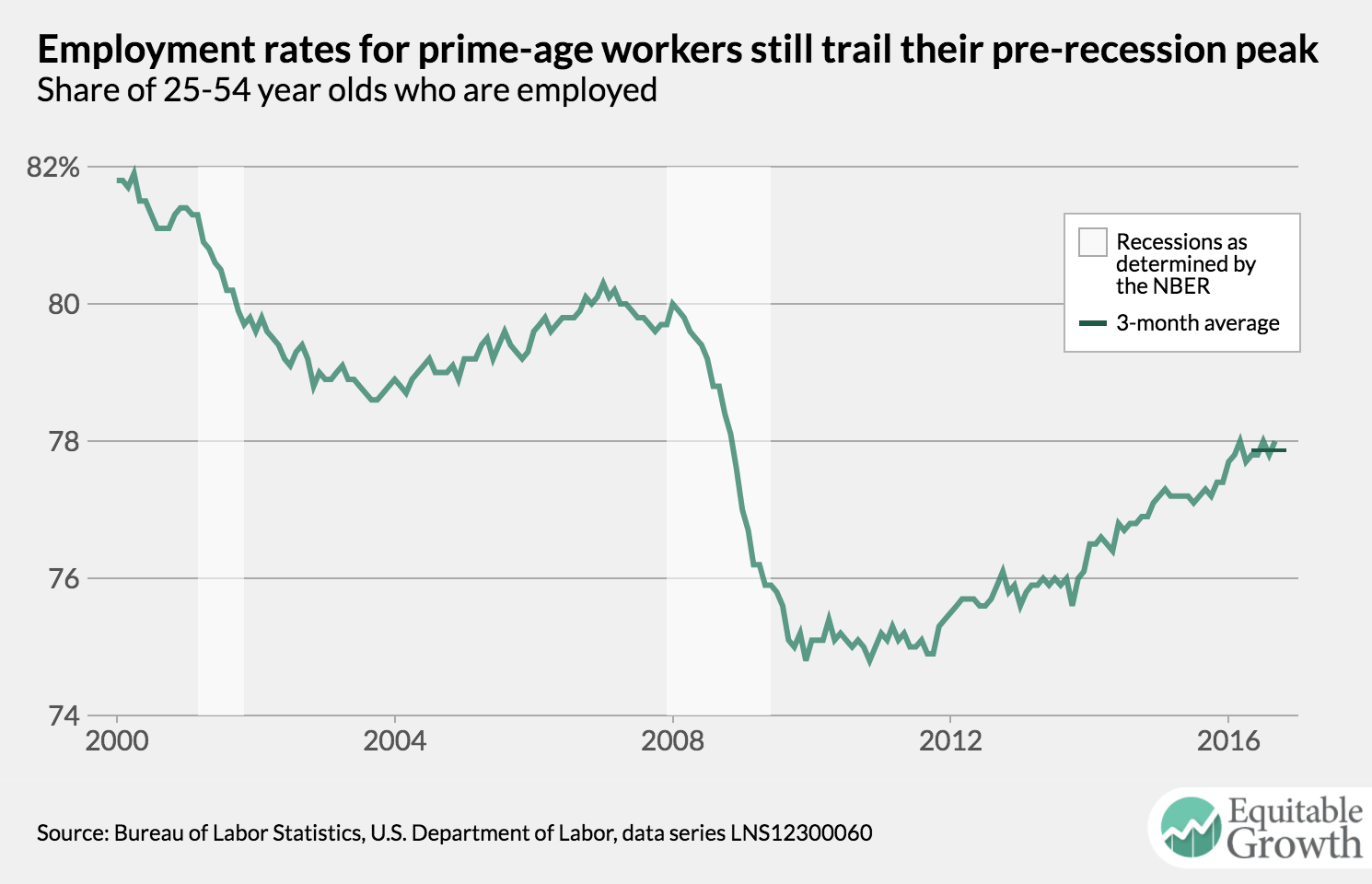

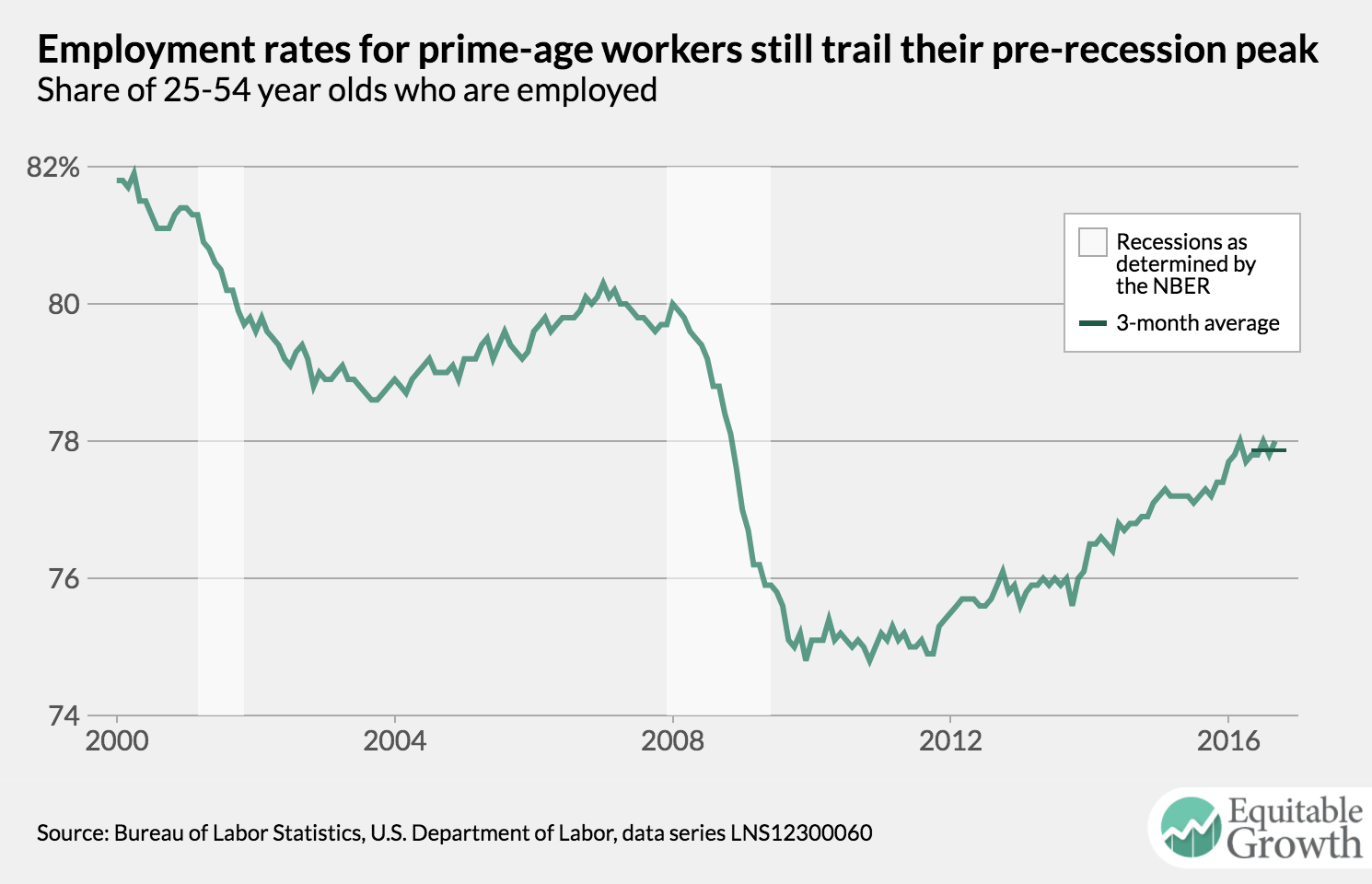

Friday figure

Figure from “Equitable Growth’s Jobs Day Graphs: September 2016 Report Edition”