This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is the work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Why hasn’t the Federal Reserve tried overshooting inflation or economic growth? Nick Bunker considers whether the hesitancy lies with the central bank’s target or believes about how quickly inflation might rise.

“Labor’s share of income” refers to the share of national economic output that workers get as compensation in exchange for their labor. It began to decline in the United States around the turn of the 21st Century and similar trends have been observed in multiple other countries, but we still don’t conclusively know why. One potential explanation comes from Princeton University economist and Equitable Growth-grantee Ezra Oberfield, who, in a recent submission to Equitable Growth’s Working Paper Series, argues that the decline in labor’s share of income could in fact be due to the slowdown in productivity growth that has also been observed in recent decades.

In a new column cross-posted from VoxEU, Oberfield and his co-authors break down their paper’s analysis and key findings.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released its latest U.S. labor market report for February this morning. Check out five key graphs from the new data compiled by Equitable Growth staff.

Links from around the web

Women’s participation in the labor force is enabled by care work, which is one of the lowest paid sectors in the U.S. economy and continues to be disproportionately provided by women of color. And care workers need to be able to spend time with their own families, too. These are all things that advocates for paid leave need to take into consideration when designing policy to ensure that everyone is able to take advantage and benefit from paid leave. [slate]

In a new bill introduced this week, Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) aims to ensure that workers share in the benefits when their companies do share buybacks. [vox]

Why are state tax dollars subsidizing corporations? University of Texas-Austin professor and Equitable Growth-grantee Nathan Jensen asks this question in an op-ed in The New York Times. [nyt]

Read more about Jensen’s work on government subsidies for economic development, including in his working paper on the subject for the Equitable Growth Working Paper Series.

Research into the effects of cash transfer programs in other countries finds that giving poor families money improves children’s chances of success later in life across a range of measures, including working more hours per week as adults than similarly poor children whose families didn’t receive the cash. [the atlantic]

In an op-ed for the The New York Times, Columbia University professor Alexander Hertel-Fernandez and Brookings fellow Vanessa Williamson—both Equitable Growth grantees—explain the results of their new research into the impact of “right to work” laws on voter turnout and election results.

The Great Recession revealed the connection between household debt and the business cycle. Economists Atif Mian of Princeton University and Amir Sufi of the University of Chicago—both Equitable Growth grantees—explain how expansions in credit supply interact with household demand to drive the business cycle and the implications of this for the relationship between inequality and the economy. [project syndicate]

You can also read more about Mian and Sufi’s working paper on the subject in this Value Added post by Equitable Growth’s Nick Bunker.

Friday figure

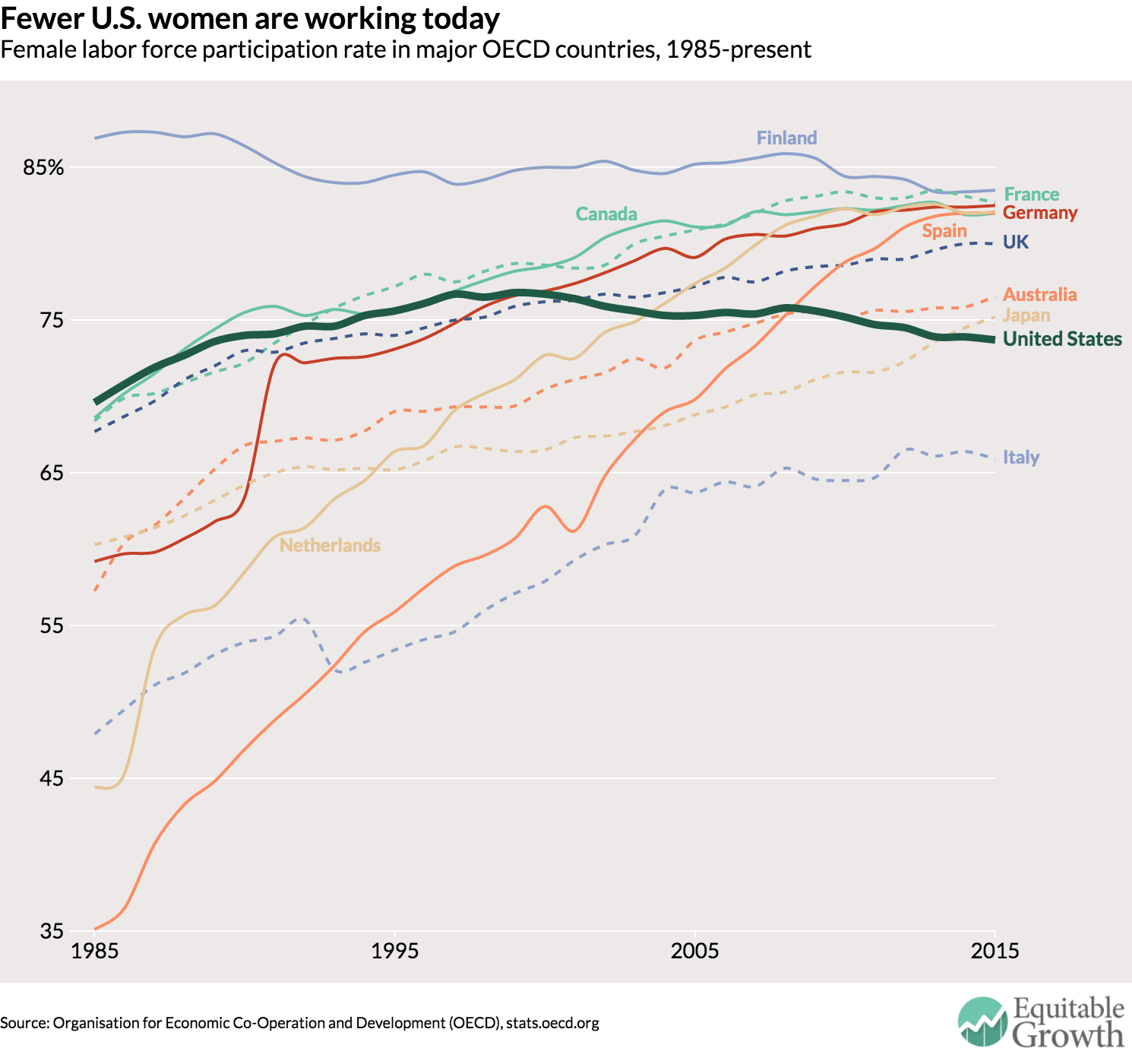

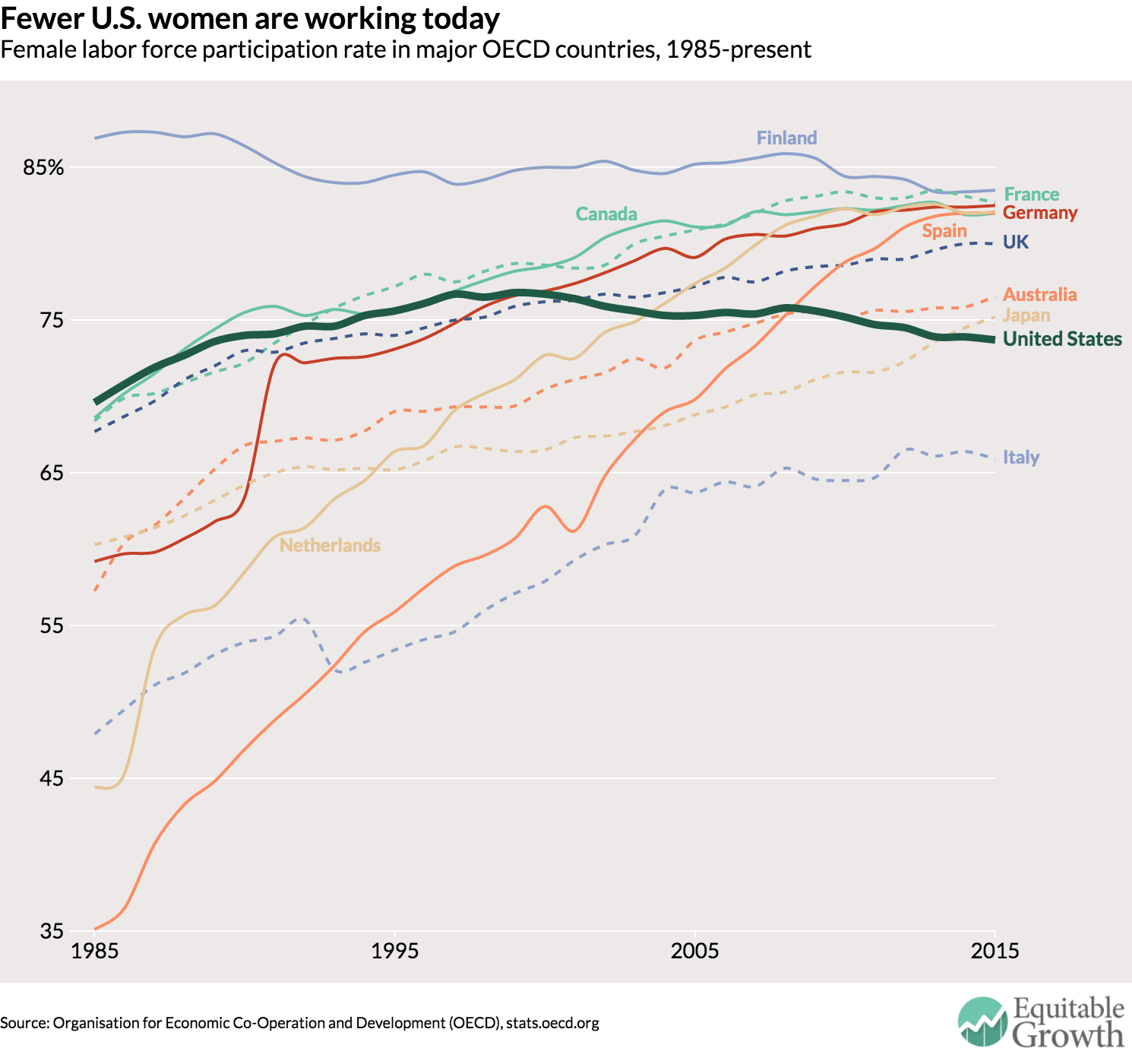

In honor of International Women’s Day, which was March 8:

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s, “Is the cost of childcare driving women out of the U.S. workforce?”