This week, Congress is beginning to take steps to repeal the Affordable Care Act. New research shows that repeal could have significant consequences for U.S. income and health inequality. The research estimates that 22.5 million people could be uninsured by 2019, swiftly reversing the gains in health equity over the past three years, while those at the tippy top of the income ladder would reap hundreds of thousands of dollars in income gains.

Let’s first examine the U.S. income inequality projections. According to recent microsimulation model calculations produced by the Tax Policy Center, repealing all of the Affordable Care Act’s tax provisions would, on average, reduce households’ taxes by $180, increasing after-tax income by 0.3 percent in 2017. A longer-term forecast to 2025 estimates that the average household would save $530 in taxes and see 0.6 percent gains in their after-tax income.

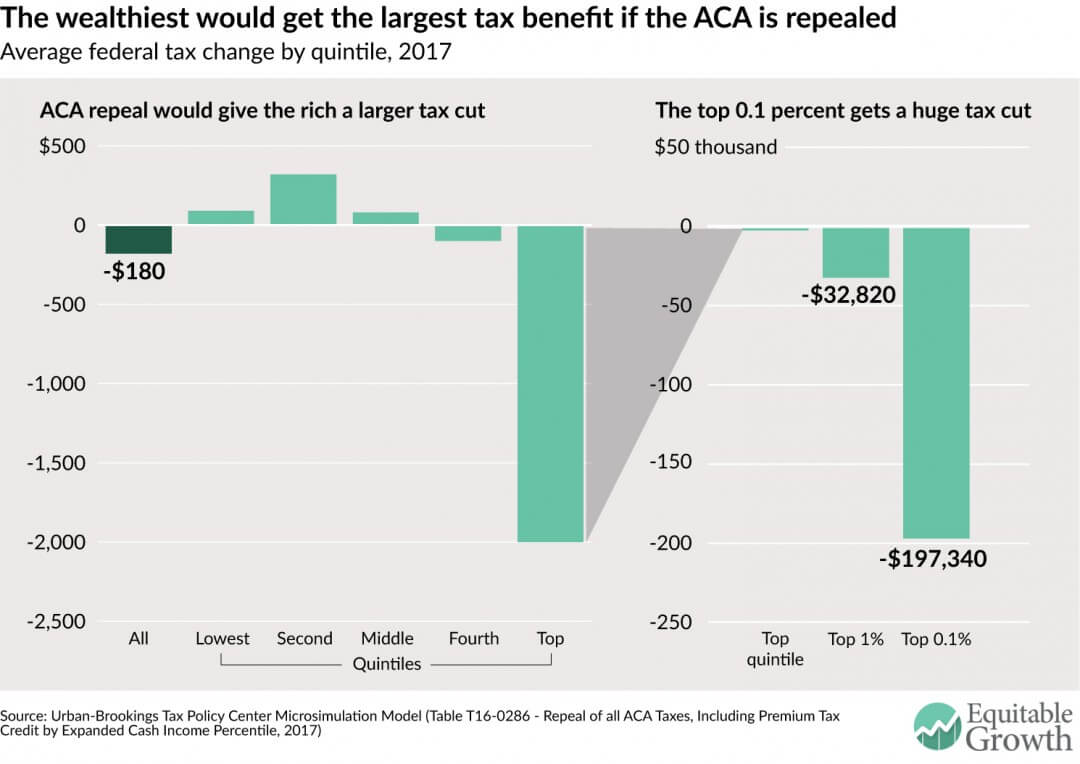

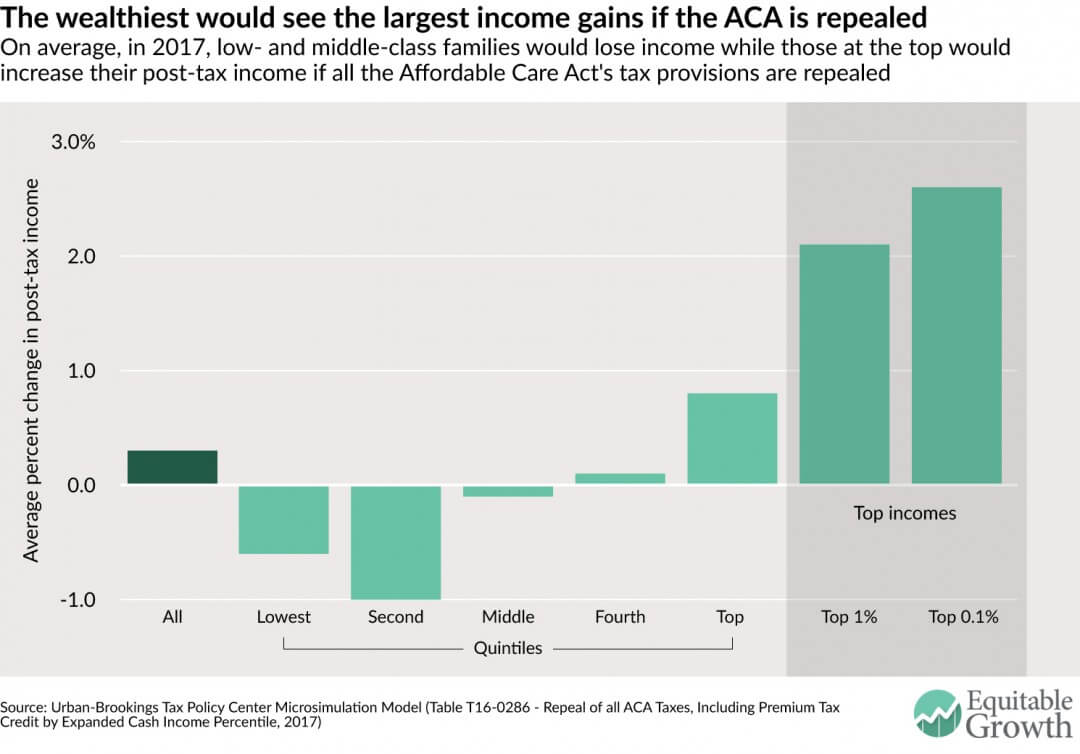

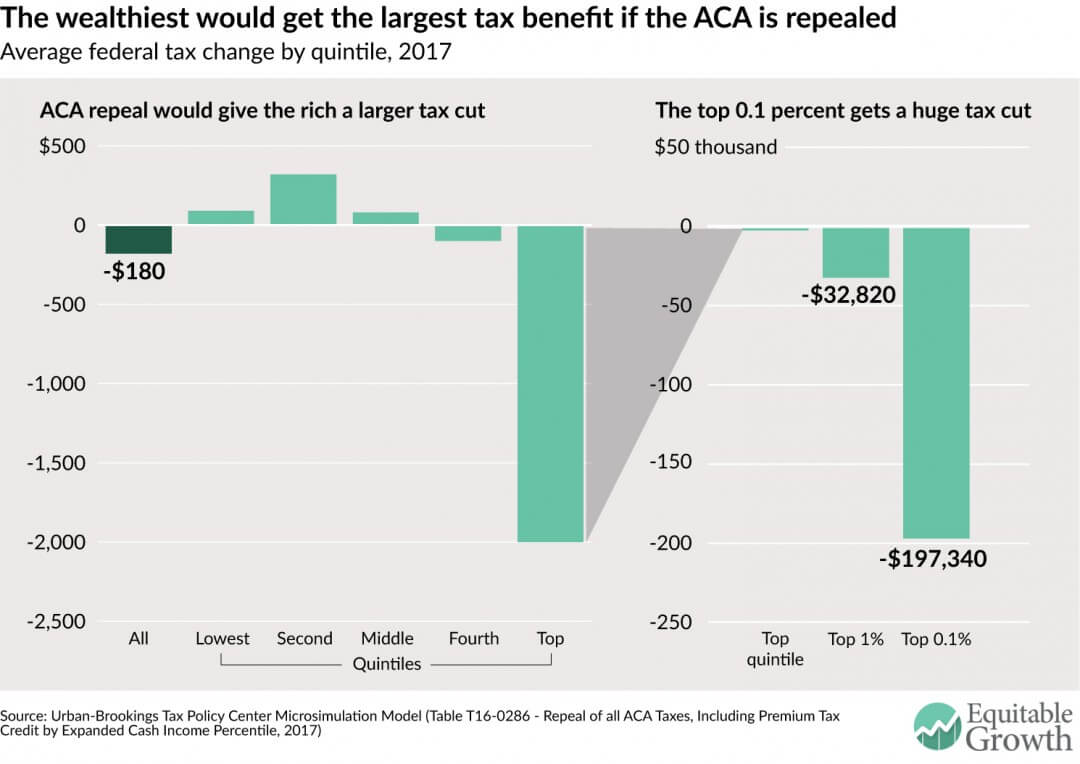

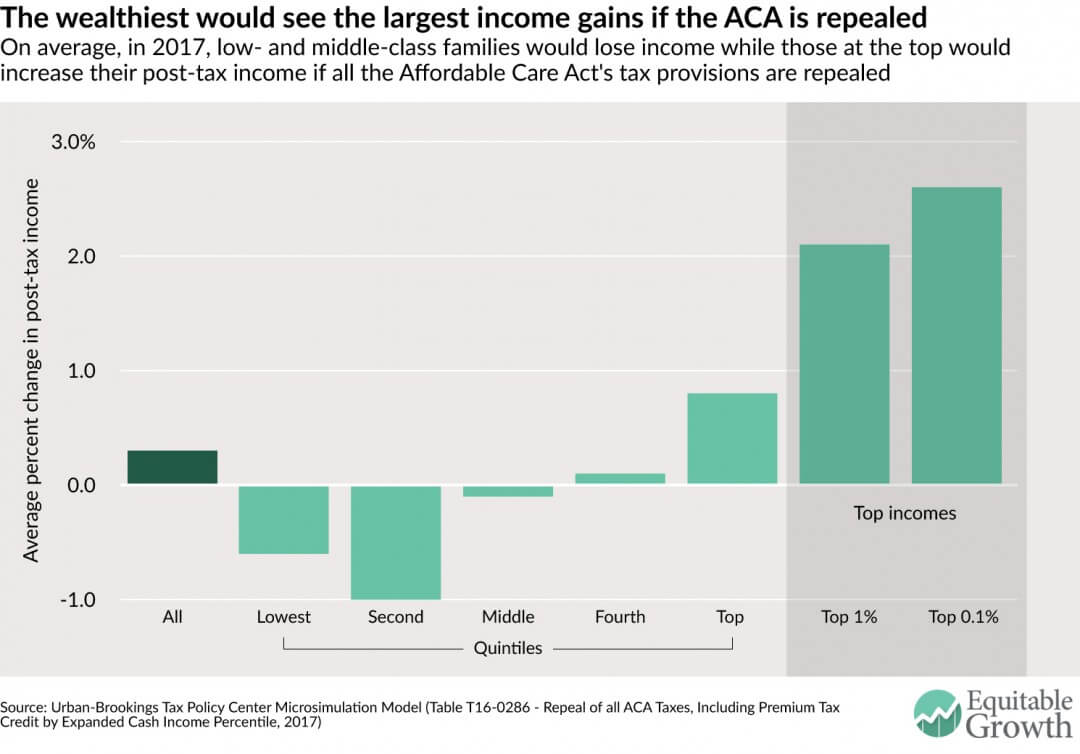

Looking across the entire income spectrum, though, reveals more detail about who really benefits from these tax cuts. (See Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1

Figure 2

In 2017, U.S. households in the bottom three income quintiles—those earning less than $24,800, between $24,800 and $48,000, and between $48,000 and $83,300—would, on average, actually owe $90, $320, and $80, respectively, more in taxes. In other terms, these low- and middle-income households would lose 0.6 percent, 1.0 percent, and 0.1 percent, respectively, of their after-tax incomes. These projected changes can largely be attributed to the potential elimination of the Premium Tax Credit provision, which is designed to help low- and middle-income families pay health insurance premiums for plans purchased on the Marketplace.

Further up the income ladder, richer households would disproportionately benefit from a repeal of the Affordable Care Act. This is because any repeal of the Affordable Care Act is expected to include the removal of the 0.9 percent Additional Medicare Tax and the 3.8 percent Net Investment Income Tax, both of which apply only to individuals with an income above $200,000 or couples with an income above $250,000. In 2017, households in the top income quintile—those making more than $143,100—would see an average tax cut of $2,000 (or a 0.8 percent increase in post-tax income). At the top one percent of the income ladder, households earning more than $699,000 would save $32,820 in taxes, while those multimillionaires earning more than $3,749,600 (the top 0.1 percent) would save a whopping $197,340 in taxes. This equates to a 2.1 percent and a 2.6 percent after-tax income increase for the top one and top 0.1 percent, respectively.

The Tax Policy Center’s analysis of repealing the Affordable Care Act raises even more concerns about widening disparities between low- and middle-income families and those at the very top, especially given what we know about income inequality. Recent research by University of California-Berkeley’s Emmanuel Saez, for example, demonstrates that while the incomes for the bottom 99 percent of families grew since the Great Recession—and increase of 3.9 percent—the top one percent of families experienced a 7.7 percent increase in their income. Another working paper by Saez, Paris School of Economics’ Thomas Piketty, and UC-Berkeley’s Gabriel Zucman finds that there has been a surge in pre-tax income inequality. And repealing the Affordable Care Act would cause serious ramifications for post-tax income inequality, too. The three economists’ working paper highlights that the top one percent’s share of national income has been rising whether you are looking at before- or after-tax income levels while the share for the bottom 50 percent has experienced significant declines.

Then there are the projections of rising health inequality. The repeal of the Affordable Care Act would place the individual- and employer-sponsored insurance mandates and the expansion of Medicaid in jeopardy. In a new report, Linda Blumberg, Matthew Buettgens, and John Holahan of the Urban Institute find that between erasing the individual insurance mandate, Medicaid expansions, and the Premium Tax Credit, 22.5 million people would become uninsured by 2019. Uninsurance could mean more out-of-pocket expenditures and could lead to larger disparities in health outcomes, particularly for the low- and middle-income families and other vulnerable groups most at risk of losing their health insurance through a repeal.

There are still many uncertainties about how the process of repealing the Affordable Care Act will play out in Congress and how many of its provisions will be replaced, discarded, or reformed. The Affordable Care Act is unlikely to be repealed in full because Congress plans to use a process known as budget reconciliation that will only allow for changes to be made to the components of legislation that have direct implications for tax, spending, revenues, or the federal debt limit.

Within the Affordable Care Act, there are only a handful of items that are connected to the federal budget. This means elements such as protections for individuals with preexisting conditions and essential health benefit requirements could stay intact. But the easiest targets for repeal through budget reconciliation include the tax and spending provisions that, if removed, would end up exacerbating income and health inequalities in the United States. Without a replacement option for the Affordable Care Act lined up to address the gaps left by these key provisions, ensuring equity in economic and health outcomes for all Americans will be challenging.