Must-Read: It’s not just “pop economics” by “pop economists”. It’s bad economics by senior and (formerly) well-respected economists. Why Lucas, Fama, Prescott, Cochrane, Taylor, and all the other cheerleaders for fiscal austerity have not paid a big reputational price for their astonishingly transparent and obvious analytical blunders–what David Romer called “Econ 1-level analytical blunders” still astonishes me:

Noah Smith: The Ways That Pop Economics Hurt America: “Someone needed to write a book about how economic theory has been abused in American politics…

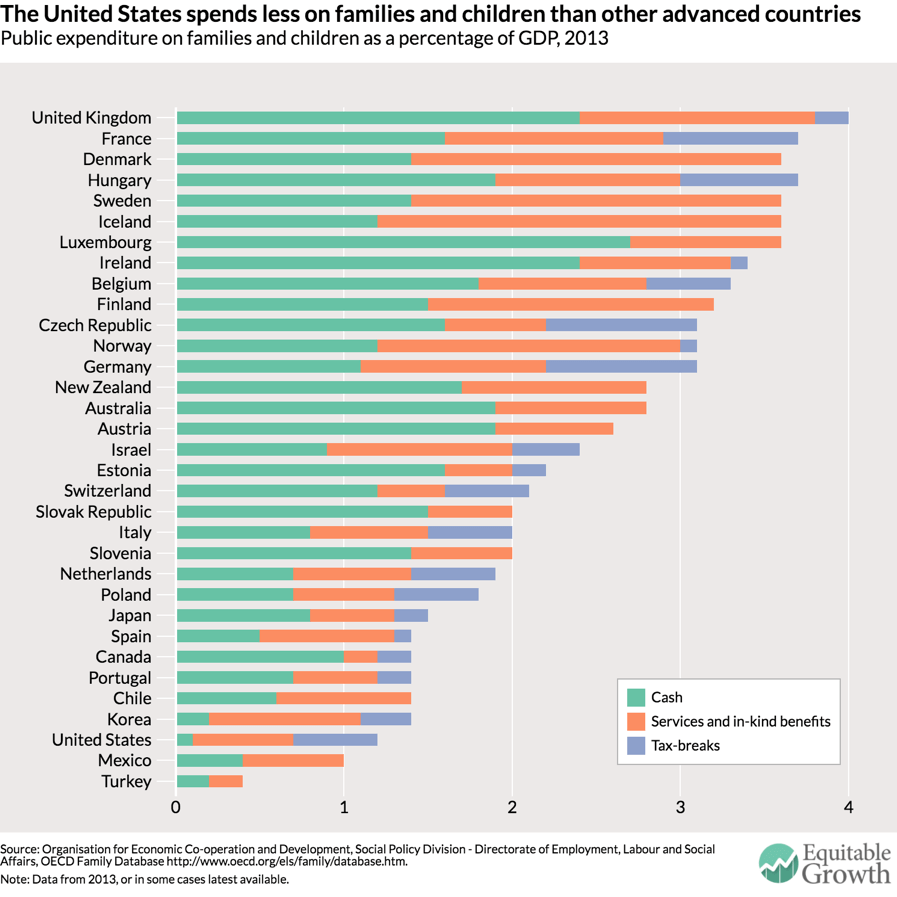

…And someone finally did. James Kwak’s “Economism” is a very important and timely book, and anyone who is interested in public affairs should pick up a copy and read it. Kwak… spins a tale of how simple supply-and-demand theory fed a free-market ideology that led to a financial crash, a dysfunctional health-care system, spiraling inequality and a threadbare social-safety net…. With Econ 101 as the default lens through which everyone views the world, Kwak argues, government programs and regulations start to seem dangerous and inefficient, while inequality begins to feel like the natural and just order of things. There is much truth here. When competitive free markets and rational well-informed actors are the baseline assumption, the burden of proof shifts unfairly onto anyone proposing a government policy….

Simple theories… we learn in our formative years… maintain an almost unshakeable grip…. Supply and demand… doesn’t work very well for labor markets… is incapable of simultaneously explaining both the small effect of minimum wage increases and the small impact of low-skilled immigration. Some more complicated, advanced theory is called for. But no matter how much evidence piles up, people keep talking about “the labor supply curve” and “the labor demand curve”… and… analyz[ing] policies… using the same old framework. An idea that we believe in despite all evidence to the contrary isn’t a scientific theory — it’s an infectious meme.

Academic economists are unsure about how to respond to the abuse of simplistic econ theories for political ends. On one hand, it gives them enormous prestige…. But as Kwak points out, the simple theories promulgated by politicians and on the Wall Street Journal editorial page often bear little resemblance to the sophisticated theories used by real economists…. The solution–which Kwak discusses, and which I endorse–is empirical evidence…. The cure… isn’t less economics–it’s more and better economics….

Why was economism… so successful?… Kwak chalks it all up to the purposeful influence of business leaders, the wealthy and their enablers…. [But] it seems clear to me that the real-world usefulness of a worldview or ideology really does have an effect. Russia and China have given up communism not because they stopped having working classes, but because it became obvious that their communist systems were keeping them in poverty…

As somebody who watched the war against Bernanke, the war against fiscal stimulus, and before that the wars on regulation of housing finance and the earlier war on Card and Krueger and their minimum wage studies, I think James Kwak has it right: the rich fund the lazy and ideological, and those who aren’t originally lazy and ideological fall into being so given the rewards offered…