A look at overwork in three charts

The House Education and Workforce Committee is holding a hearing today on Capitol Hill to examine several aspects of the Obama Administration’s announcement earlier this month that it would require overtime pay for most salaried employees making less than $46,476—a massive expansion of those eligible for overtime pay. The U.S. Department of Labor estimates that the new ruling will affect 4 million workers once it is implemented on December 1, with others estimating even more.

In our recent report, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth examined the causes and consequences of long work hours, a key part of the overtime debate. Below are a few graphs from the report:

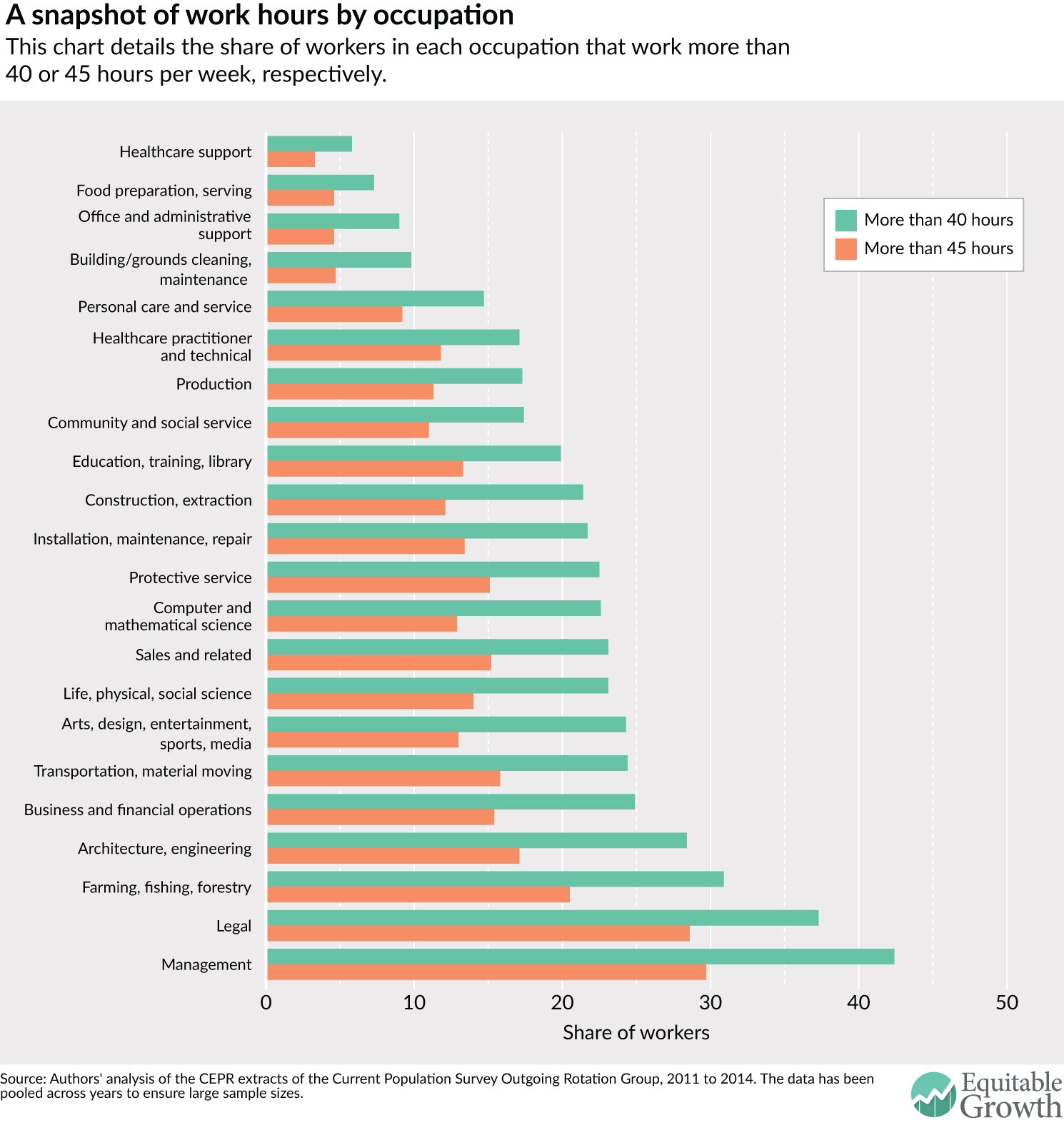

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows the occupations with the share of workers working more than 40 hours and those working more than 45 hours per week on average. The legal and management occupations have the highest share of employees putting in long hours: 28.6 percent of legal workers and 29.7 percent of management workers put in more than 45 hours a week. They are followed by farming, fishing, and forestry (20.5 percent); architecture and engineering (17.1 percent); and business and financial services (15.4 percent). These occupations also have a high percentage of employees working more than 40 hours a week.

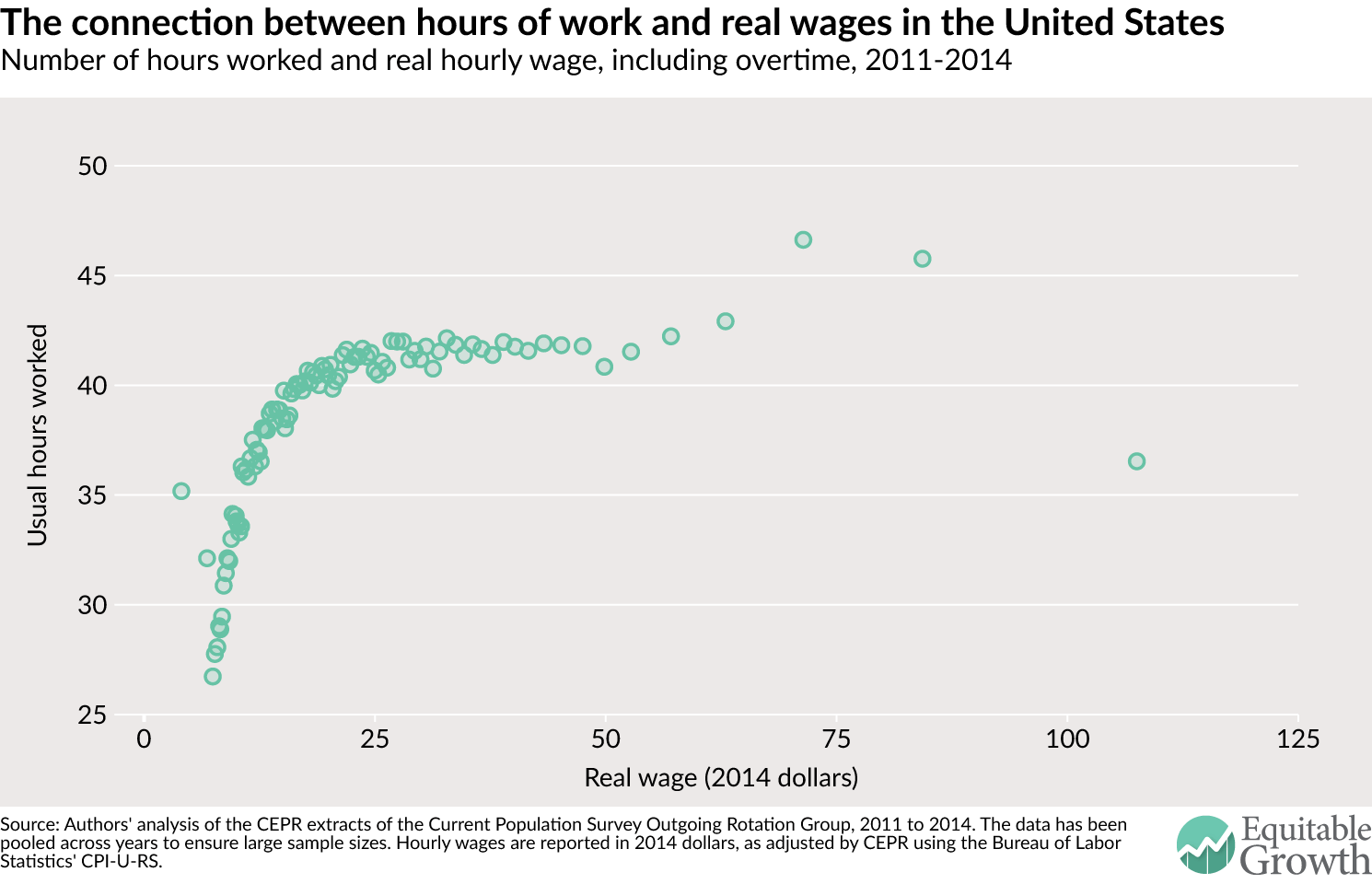

While many of these occupations are relatively high-paying, it is not just the highest-earning families who work long hours—not by a long shot. Figure 2 shows that a worker’s hourly wage does increase as they work additional hours, also long as they work fewer than 40 hours a week. But after the 40-hour threshold, the return of additional hours of work – higher hourly wages – isn’t clear. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

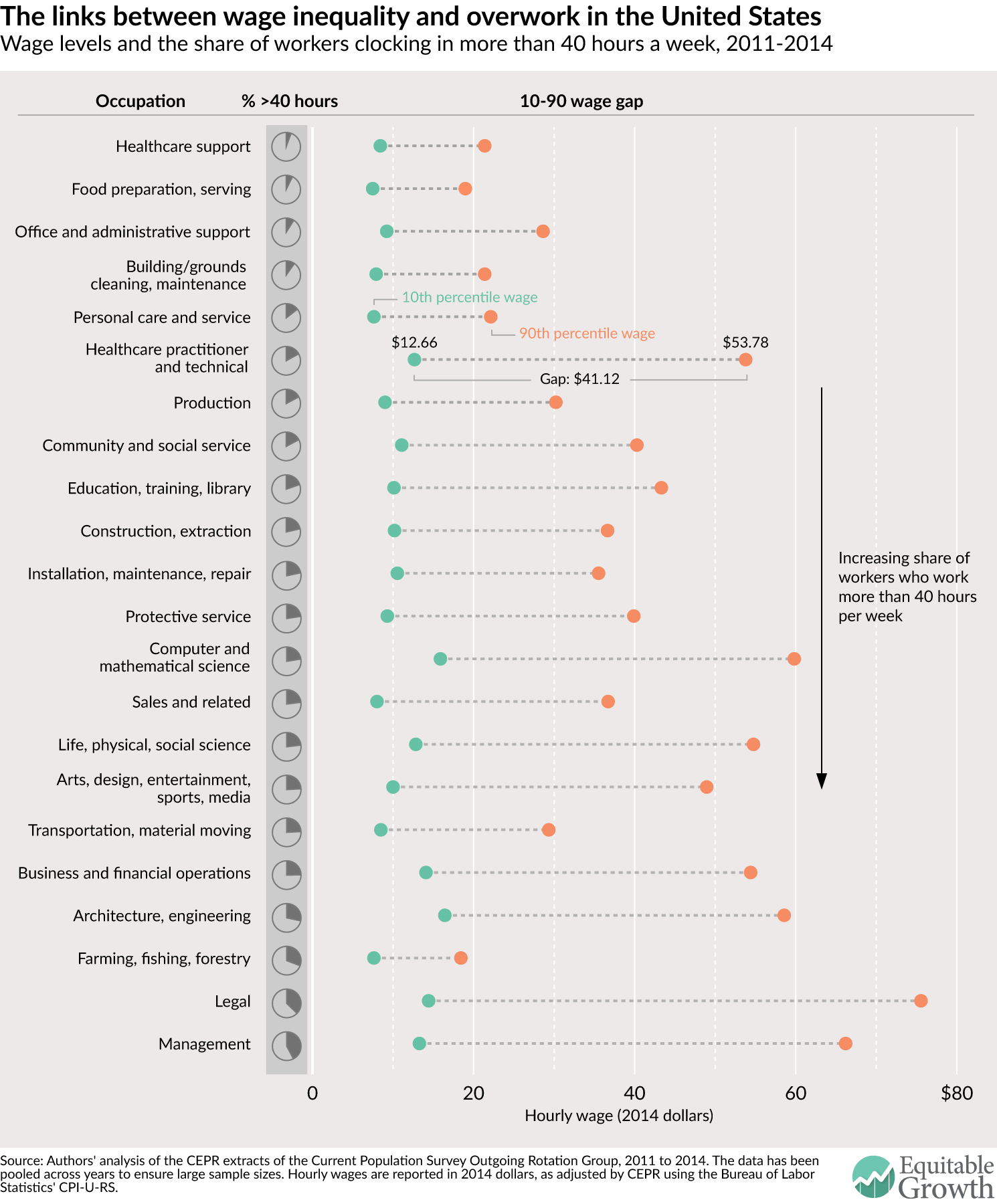

Our report examines data that also shows occupations with a high level of wage inequality tend to have a larger share of employees working more than 40 hours a week. While this is not the case across every occupation, within many professional occupations—architecture and engineering, computer and mathematical science, legal, and business and finance operations—there is both a high share of workers putting in long hours as well as a large gap between the 10th and 90th percentiles of the wage distribution. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

As we laid out in the report, rising economic inequality may be one cause of long hours—even for those near the top of the income and wealth ladders. In recent decades, employers have been downsizing their labor force—a trend exacerbated by the Great Recession that began in 2007 as employers laid off a massive number of employees while demanding more from those who survived. As work became more precarious, many salaried workers lost the bargaining power to demand compensation for the increase in hours. As competition for jobs grew, spending extra time in the office increasingly feels like a small price to pay even for those who are exempt and do not receive extra pay.

Scholars have found that, over time, the long work hours become embedded in certain organizational and workplace cultures. Within professional, white-collar occupations, there may be a greater element of individual control and choice over one’s work hours compared to blue-collar occupations. But researchers note that the “choice” to work long hours is heavily influenced by a number of social, economic, and psychological factors. As a greater number of workers within some professions put in longer hours, a culture of overwork becomes entrenched in the workplace culture. This phenomenon has spillover effects as the long hours create the need for 24/7 services to support those who cannot do their shopping during the Monday-Friday workweek or who need child care early in the morning or late at night. Thus, long hours for professionals trickle down into non-traditional hours for service workers.

=We’ve all heard the common success story, that of the successful lawyer, banker, businessman, or doctor who counsels young professionals that an extreme work ethic is key to their success.

There is no doubt that success cannot be had without hard work. But arbitrarily increasing work hours can also backfire for individuals, firms, and the U.S. economy alike. Extending the regulation of overtime pay and hours worked to a larger group of workers will make employers think twice before mandating long hours, and will help create a more pragmatic approach to work hours that is mindful of consequences of working without restriction.