A glance at pay inequities for African American women’s Equal Pay Day

Today marks African American women’s Equal Pay Day, which represents the day that black women must work to in 2017 to make the same amount of money that men (of all races ) did in 2016. For African American women that’s nearly an additional eight months of earning on average 63 cents for every dollar earned by a man last year. Although women (of all races) are paid 80 cents for every dollar men are paid, the wage gaps for African American women and women of color are dramatically wider—only the wage gap for Asian American women is smaller than that of white women. The persistent gender wage gap continues to harm women, their families and the larger economy, but it is particularly damaging for African American women.

Persistent pay inequalities for African American women and women of color have far-reaching economic consequences. Lower pay lowers demand, which drags down economic growth. And to the extent that women are not employed in jobs that make the most of their skills and talents, this also drags down growth by reducing productivity.

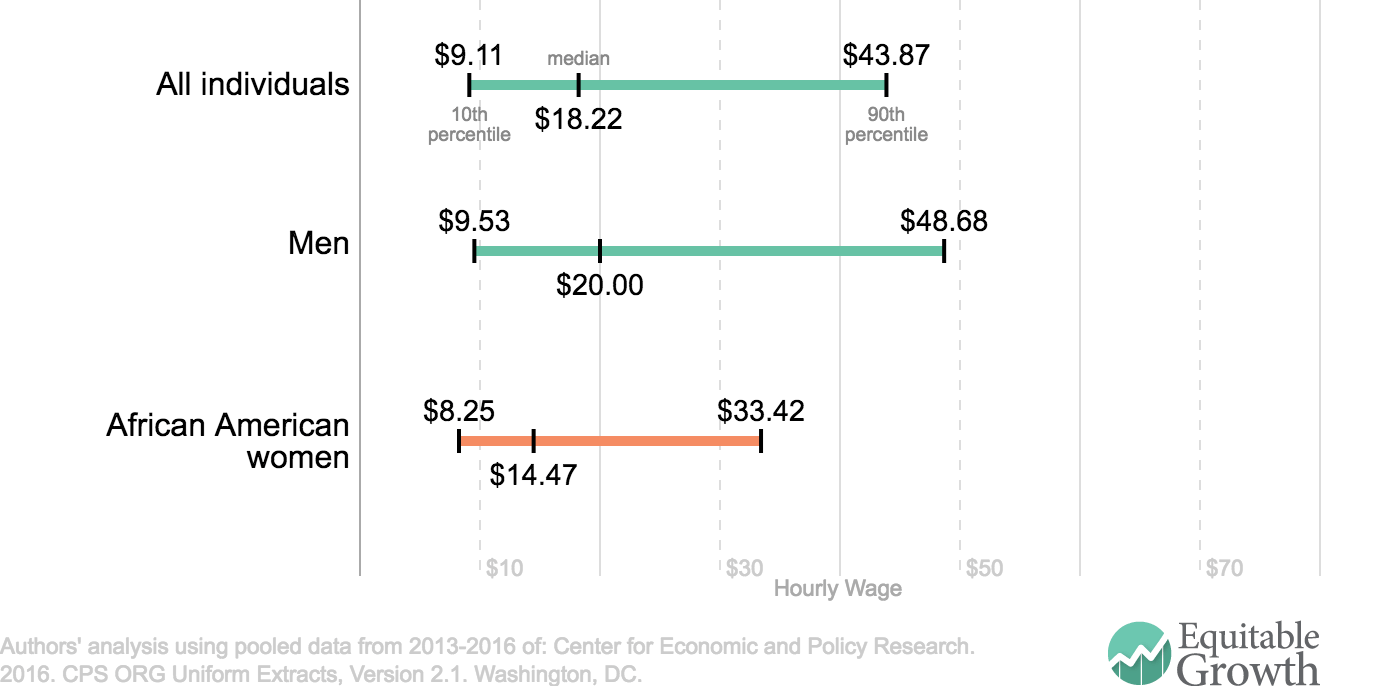

We’ve updated Equitable Growth’s interactive tool with new data to compare wages within and across demographic groups in the United States. Our updated numbers continue to show that women, and even more so African American women, continue to earn considerably less than men. The data show that men earn a median wage of $20.00 per hour, while African American women earn a median wage of $14.47. The $5.53 difference constitutes a pay gap of approximately 38 percent relative to African American women’s hourly wage rate. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Looking more closely at the wages across the distribution, we see that men get paid more at each decile. Men earning low wages make an average of $9.53 per hour compared to an average wage of $8.25 earned by African American women at the low end of the pay scale, a pay gap of about 15 percent. At the high end of the earnings distribution, the pay gap is considerably wider, approximately 46 percent, with men earning $48.68 and African American women earning $33.42. The data illustrates that the pay gap between men and African American women is more narrow at the 10th percentile for low-wage workers and widens for workers as they move up the wage distribution.

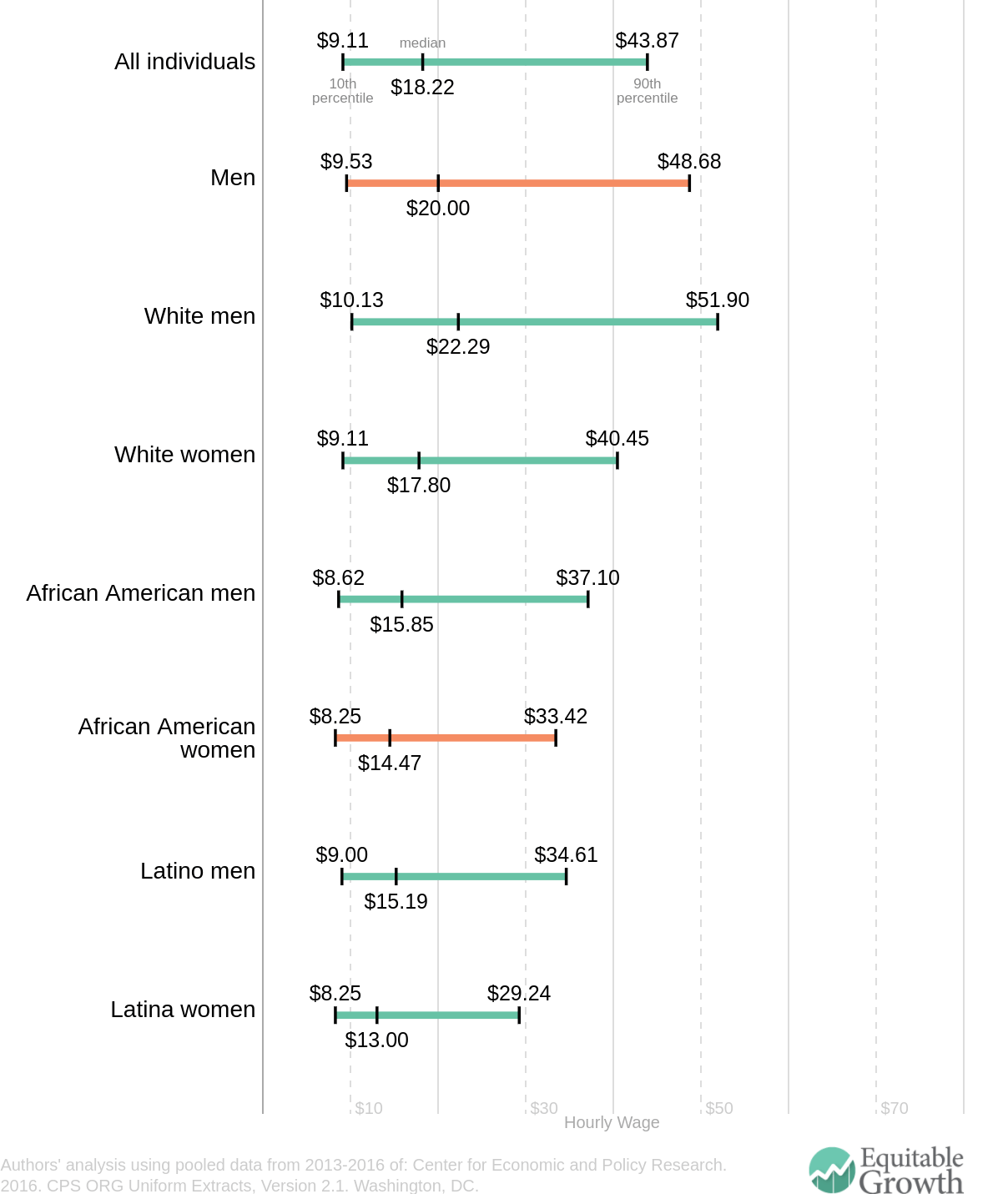

When we look at the wage distributions for different genders, races, and ethnicities, we see the same pattern of widening pay gaps as a worker moves from low-wage to high-wage work. Men earning low wages make $9.53 per hour compared to a wage of $8.25 earned by African American women on the same pay scale, a pay gap of about 15 percent. At the high end of the earnings distribution, the pay gap is considerably wider, approximately 46 percent, with men earning $48.68 and African American women earning $33.42. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

At the lower end of the wage distribution, workers from different demographic backgrounds have relatively similar wages. Latina and African American women earning low wages average the least pay, $8.25 per hour, while white men at the same pay level earn the most, $10.13. This cluster of wages at the bottom is likely in part due to minimum wage laws, which provides a wage floor for workers and shrinks the dispersion of wages at the bottom.

For workers who earn middle-range wages, the gender gap grows. Latina and African American women at the median earn the least of these groups, earning on average $13.00 and $14.47 per hour, respectively, while white men earn $22.29. At the top of the earnings distribution, the wage gaps are the largest— $29.24 for Latinas, $33.42 for African American women, but $51.90 for white men)—a difference of nearly $20.00 per hour.

This scattering of top wages reflects discrimination across both gender and race in the U.S. labor market. The pre-exisiting cultural and social norms we observe such as occupational segregation and the lack of family friendly policies in the workplace keep women from obtaining and holding onto high paying jobs. And racial discrimination within hiring practices and other labor market interactions play a large role in leaving workers of color behind. African American and Latina women are most disadvantaged as they experience both sets of discrimination at work.

Increasing educational attainment levels for all women of color, as is commonly suggested, has not proven to shrink the gender wage gap. Over the past few decades women received more college and graduate degrees than men and African American women’s college enrollment has accelerated. Despite this rise in educational attainment, African American women still earn less, experiencing a wage gap at every educational level.

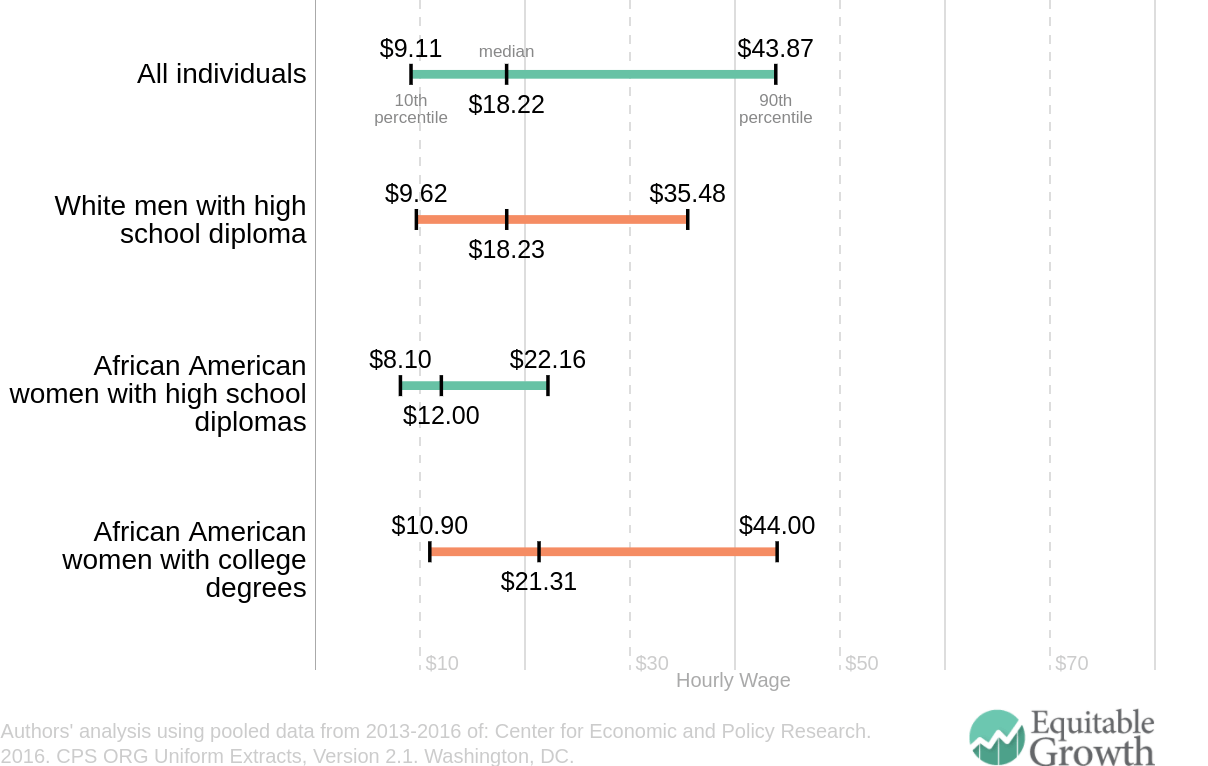

Studying the wage distributions of workers by their level of educational attainment highlights this mismatch. By comparing the earnings of white men with high school degrees to African American women with college degrees we demonstrate that the return to a college degree for African American women is not enough. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

White men with high school degrees make about $9.62 per hour at the low end of the pay scale, only 13 percent less than African American women with a college degrees, who earn $10.90. In the middle, white men with a high school degree earn $18.23 per hour, or 17 percent less than the median African American women with a college degree, who earn $21.31. And even at the top of the wage distribution, the pay gap between white men with high school degrees and African American women with college degrees is only 24 percent.

Raising the minimum wage at the federal, state, and local levels would help compress the pay gaps we observe between workers in different demographic groups. This data, however, show that we need to focus on workers higher up the income ladder. Policies to mitigate workplace discrimination, increase worker bargaining power, and family friendly policies would also help reduce pay inequities for women of color. Until we address structural sexism and racism, they will continue to have negative economic consequences for these groups of workers unless addressed by our broader community.