Countering right-wing populism: Identifying its cultural roots and charting a path forward

Overview

Donald Trump’s victory in the 2024 U.S. presidential election set off an animated debate among Democrats over what went wrong with their policymaking, messaging, and campaigning. Specifically, Democrats puzzled over why the working class abandoned the historical party of workers in ever-larger numbers, seemingly in favor of President Trump’s populist message.

Much of this debate has centered on the electoral failings of “Bidenomics,” the economic policy approach pursued by the Biden-Harris administration. Some pundits argue that Bidenomics did not sufficiently re-balance the U.S. economy to address the hardships of the working class, while others criticize it for stimulating higher inflation through increased spending, thereby hurting the very working-class voters that the president desperately sought to win over.1

Looking for a path forward, the need to settle on an economic agenda for governing after President Trump’s second term in office is surely an important endeavor. But as a formula for countering the appeal of right-wing populism, it misses much of the point.

Importantly, the rise of populism and its electoral successes are not confined to the United States or a few of its recent elections. In fact, over the past two decades, a slew of other advanced democracies around the world also witnessed a resurgence of populism, a political movement defined by its opposition to elites and its claim to represent the “true people.”

From the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom and the surge of the National Rally in France, to Italian President Georgia Meloni of the Brothers of Italy’s takeover and the rise of the AfD in Germany, right-wing populism has emerged as a powerful force, disrupting political norms and reshaping electoral landscapes. To effectively counter President Trump’s widespread appeal in the United States thus requires a better understanding of the underlying causes of this (predominantly right-wing) populist wave around the globe. Yet despite its global character, the antecedents of modern right-wing populism remain a subject of deep disagreement.

A central point of contention is whether economic or cultural factors instigated the populist wave. Economic-centered arguments emphasize the role of globalization, automation, and global financial crises in generating widespread dislocation and economic insecurity, fueling a sense of resentment upon which populists have capitalized. In contrast, cultural explanations for the success of populism focus on societal changes. Higher rates of immigration and growing diversity, they argue, in addition to urbanization and a shift to more progressive values on cultural issues, have generated a backlash among those who perceive such developments as a threat to their identity and way of life. Seizing on this discontent, populist parties attracted growing numbers of voters.

The dichotomy of explanations is problematic because the two forces—economic and social-cultural—are intertwined. But understanding the relative importance of the different causes and correctly identifying the roots of popular disaffection is key because it carries weighty implications for the positions and policies that elected officials should pursue to effectively counter the appeal of right-wing populism both in the United States and abroad.

I contend that the role of economic insecurity in explaining populism is quite different from the one attributed to it in conventional wisdom. While economic factors are sometimes important in explaining electoral outcomes on the margin, they do not account for the broad support for right-wing populist issues, candidates, and parties. That support should instead be understood predominantly as a result of anxiety about cultural and demographic shifts and people’s sense that core aspects of their identity are under threat. These cultural dimensions are connected to economic transformations and policies, but voters’ attitudes and preferences cannot simply be attributed to their economic circumstances alone.

In thinking about the path to counter the appeal of right-wing populist candidates and parties, there’s a need to distinguish between two different questions. The first is what center-left parties should do to win in the next election. The second is how center-left policymakers can counter populism to durably regain the trust and votes of the working class and those without a college degree.

As I shall explain, these two questions may require different answers. The first question will greatly depend on the failings of the second Trump administration and the short-term openings it will provide the opposition. In this short essay I will use evidence from other advanced democracies to address pertinent, long-term implications of the latter.

The economic argument and its limitations

Economic explanations for the rise of right-wing populism have dominated much of the scholarly and public discourse. These arguments often trace populism’s roots to dislocation and economic insecurity caused by globalization (primarily via trade policies and immigration), technological change, and financial crises.2

For instance, the so-called China trade shock—a massive surge in imports following China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001—hurt manufacturing industries in advanced economies around the world, leading to significant job losses and economic pain in some regions.3 Studies have shown that these hard-hit regions showed higher levels of support for President Trump in his first presidential bid in 2016 and for populist candidates in Europe over the past two decades.4

Yet the focus on such economic drivers conflates two distinct concepts that I term explanatory significance and outcome significance. Explanatory significance refers to the role of a given factor in accounting for the overall phenomenon, while outcome significance is the marginal impact of a given driver in bringing about an observed outcome.

The adverse effects of the China trade shock, for instance, are estimated to have led to a shift of about 4 percentage points in the UK’s Brexit referendum5—just enough to secure the Leave camp’s narrow victory. In that sense, this shock had high outcome significance in that it determined the eventual election result. Yet it does little to explain why 52 percent of Britons decided to support Brexit. In that sense, those 4 percentage points have low explanatory significance for the phenomenon of interest (the support for Leave overall). This distinction is important to our understanding of the broader impact that economic insecurity plays in the populist vote.

Indeed, examination of the empirical evidence from other countries and elections indicates that the explanatory significance of economic factors, taken by themselves, is rather limited. The most in-depth empirical analyses of individual-level data consistently reveal that economic insecurity accounts for only a modest share of the populist vote. In a 2017 comprehensive study of 25 countries, for example, researchers found that an increase of one standard deviation in economic insecurity was associated with a 0.3 percentage point increase in the likelihood of voting for a populist party. Even when taking account of additional indirect influences of economic insecurity, this represents only about 7.4 percent of the overall share of the populist vote.6 Other studies that assess the effect of trade-induced economic insecurity on regional voting in Europe have revealed similarly modest effects.7

The limits of economic insecurity as an explanation for the populist surge also are evident when one examines the descriptive characteristics of the populist support base. Consider, for example, that if the data show that only 20 percent of the supporters of a populist party fit the definition of working class, then an explanation centered on “working-class economic anxiety” in that country can account for at most 20 percent of the party’s support.8

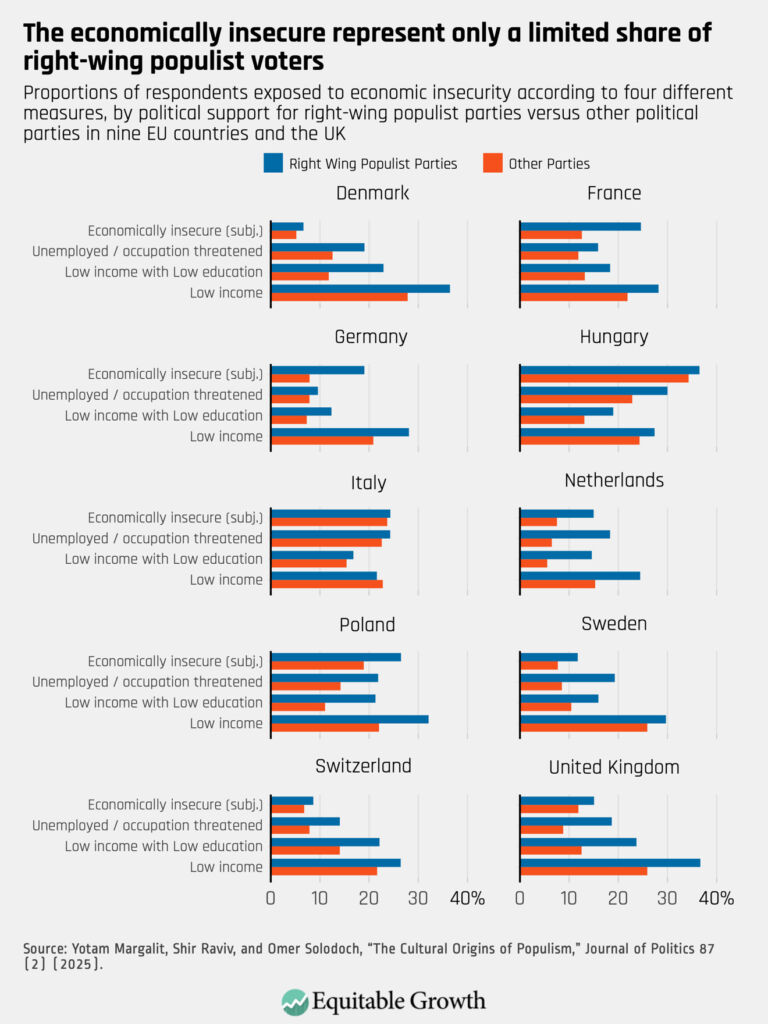

This descriptive analysis is what my colleagues and I have done using detailed survey data from Europe.9 Figure 1 below compares the share of voters that match the profile of “economically insecure” in 10 European countries, which we defined using four alternative measures: people’s subjective reports of economic hardship; being unemployed or working in the manufacturing sector; having no college degree and a low income; or only having a low income.10 We then separately examine support of right-wing populist parties versus support of other political parties. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

As expected, Figure 1 shows that higher numbers of populist voters were economically insecure than among those who voted for other parties. This is the case regardless of which measure of insecurity one uses. Yet, crucially, the data also show that in absolute terms, the economically insecure represent, at best, a limited share of the populist support base, typically ranging between 15 percent to 35 percent across countries. Low-income voters without a college degree, for example, account for, on average, only a fifth of the populist support base. Taken together, these findings indicate that economic insecurity, while not trivial, is far from being a dominant factor driving the broad support of the populist right.

Some will argue that while economic insecurity itself may be a limited factor, fears over the economic repercussions of immigration—on the availability of jobs, say, or declining wages—are crucial to driving support for right-wing populism. This view, again, does not hold empirically. While immigration itself is largely driven by market forces, voters’ opposition to immigration is only weakly rooted in economic considerations. Instead, research consistently finds that apprehension about immigration is driven far more strongly by cultural factors and identitarian concerns11—a topic which I turn to next.

The cultural roots of populism

Culture-centered explanations of populism’s global rise highlight the role of long-term societal changes in generating resentment among certain groups of voters. Based on a systematic review of the research literature, my colleagues and I identified five distinct “storylines” that capture the main cultural explanations put forth:12

- Intergenerational backlash: Elderly people who feel that traditional values have been trampled and overtaken by a post-materialist culture and politics

- Ethnocultural estrangement: Native-born citizens who fear that demographic changes and incoming waves of migration are changing their country’s cultural identity

- Rural resentment: Residents who feel excluded and looked down upon by urban elites and by policymakers who represent the interests and lifestyles of those living in big cities

- Social status anxiety: Primarily White men anxious about a decline in the privileged social status that their race, gender, or occupational standing have traditionally afforded them

- Community disintegration: People who feel isolated and alienated by the absence of a cohesive local community to which they can belong or rely upon

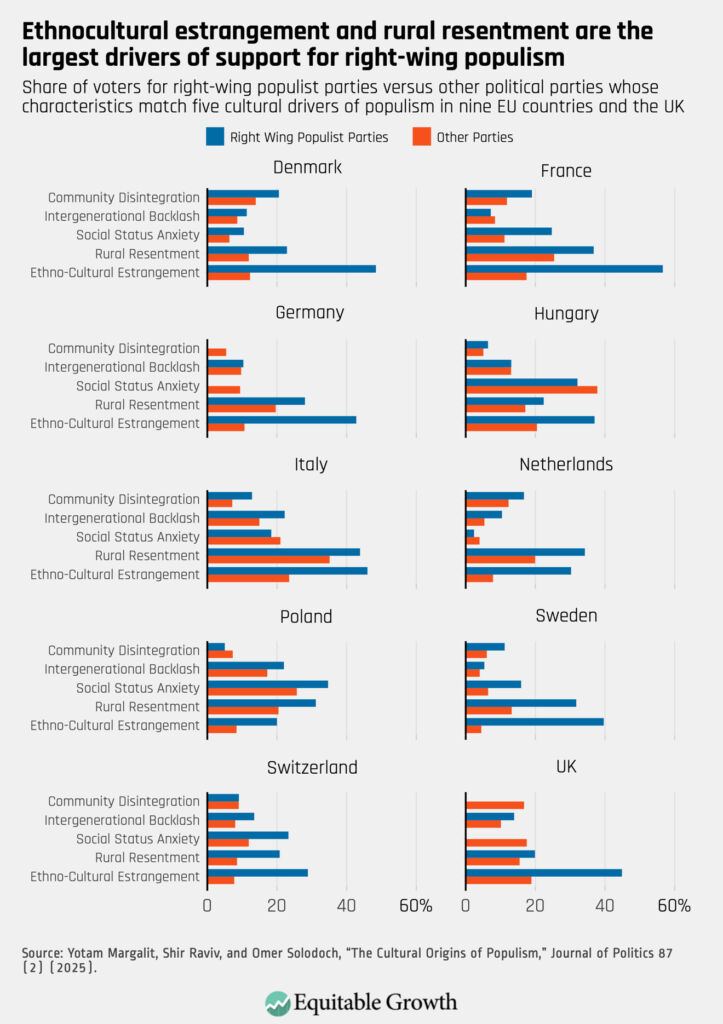

After disentangling these different accounts and laying out the social developments that underlie each of them, we assessed their usefulness across several Western democracies in accounting for support for populist parties or politicians, compared to other political parties. Figure 2 below shows that there is notable variation across the countries we studied in the patterns associated with each of these five explanations, but two drivers emerge consistently as both highly prevalent and unique among the populist base: ethnocultural estrangement and rural resentment.

Specifically, the data show that voters who match the profile associated with ethnocultural estrangement—empirically measured as native-born citizens who feel that their culture is being eroded by immigration—are particularly receptive to populist rhetoric. Additionally, resentment among rural voters is the second factor that appears to contribute most to electoral support for populist parties. This resentment stems from the growing divide between urban and rural communities, not only in terms of material resources but also in cultural recognition. It reflects a sentiment among rural residents that their interests are ignored by the decision-making elites, and that their sensibilities are looked down upon by city dwellers. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

As Figure 2 shows, in France, Poland, the Netherlands, and Germany, between 30 percent and 40 percent of populist voters match the descriptions for ethnocultural estrangement and rural resentment, compared to between 10 percent and 25 percent of voters for nonpopulists. The difference is even starker in Switzerland and Sweden.

As the United States was not part of the surveys we used to analyze European populist support, we used different data to assess the strength of the five cultural explanations, and hence the results are not entirely comparable to those from Europe. Nonetheless, the same two explanations—ethnocultural estrangement and rural resentment—were, again, the best indicators for distinguishing between people who voted for President Trump in 2016 and those who did not.

Interestingly, in the U.S. case, we also find evidence consistent with the intergenerational backlash theory, in which older voters turn to populism to defend the core values that have long informed their worldview and that they feel are being overwhelmed or eroded by modern-day culture and politics.13 We find that older people with more traditionalist values were indeed substantially more likely than other age groups to vote for President Trump.

Countering populism by addressing its cultural roots

“Liberty, equality, fraternity” is the often-used motto of the social democratic ideal. The progressive agenda has, in recent years, been defined by its preoccupation with the first two values—liberty and equality—through the prism of social justice. A focus on the third value—fraternity, or solidarity, as it is now more commonly referred to—provides an overarching goal that can tie together an effective and enduring progressive platform for countering populism’s growing appeal.

No doubt, designing policies that address cultural anxieties is a woolier challenge than addressing economic insecurity. Nonetheless, aiming for this objective is crucial. Considering the strong relationship between support for right-wing populism and sentiments associated with ethnocultural estrangement and rural resentment, the policies I discuss below primarily center on these two drivers. This is not an exhaustive list of proposals, however, as other policies could work in tandem with these to confront the different cultural factors discussed above.

Alleviating anxiety about immigration

A pertinent finding in my research is that people make a clear distinction not only between authorized and unauthorized immigration, but also between the authorized immigrants already residing in a country (the “stock”) and those expected to arrive in the future (the “flow”). Specifically, the data show that Americans tend to be more accepting of the stock but exhibit far less support for the future inflow of migrants.14

To gain credibility in controlling immigration therefore does not mean adopting a sweeping agenda that is hostile to all immigration. Standing for a stricter approach toward the flow of immigrants—by supporting stronger border control, for instance—even while opposing harsh treatment of immigrants already residing within the country—by, for example, defending the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which protects young undocumented people who were brought to the United States as children, known as “Dreamers,” from deportation—could make progress in reducing the political potency of immigration.

Research points to several other potential interventions that also may help to do so. Evidence from the United States, for example, shows that a large door-to-door canvassing campaign that consisted of “the nonjudgmental exchange of narratives” was highly effective in reducing exclusionary attitudes toward unauthorized immigrants—and did so in a lasting manner.15 There also is some evidence that inducing native-born citizens to have personal contact with immigrants can reduce hostility toward them.16

The limitation of these approaches is that they are labor-intensive and relatively costly, and the body of evidence supporting them is still small. But, potentially, programs such as national service opportunities or workplace organizing initiatives provide apt settings for such interactions, so further consideration of this approach is warranted. Indeed, a study in Norway shows that military service is effective—via shared rooming with ethnic minorities—at increasing trust in immigrants.17

Information campaigns, in which citizens are given relevant information and facts about immigration—such as their actual numbers or contribution to the local economy—are easier to scale-up nationally and are cheaper to carry out. Examples of this approach include the Canadian government’s “#ImmigrationMatters” campaign. Launched in 2018, it used social media, television, and print media advertisements to promote content designed to dispel common myths about immigration and promote positive engagement between native citizens and new migrants. Germany, Australia, and Sweden also have advanced such campaigns.

To date, however, evidence indicates that the impact of information campaigns is dependent on context. In some cases the effect of providing information on the attitudes of native citizens was substantial, while in other instances, it had little impact.18 Yet given the outsized role that immigration-related concerns play in the appeal of right-wing populism, an all-of-the-above approach should be a priority for center-left policymakers.

Revitalizing rural communities

Addressing rural resentment no doubt requires targeted investments in exurban areas to create high-quality jobs and enhance access to government services. Crucially, however, research indicates that economic revitalization of these areas is not enough.

Indeed, the closure of village halls, libraries, post offices, and parks has hollowed out many rural communities, removing key hubs where people once gathered in their communities. Evidence from the United Kingdom links this social fragmentation to rising political discontent, showing, for example, that communities that lost local pubs exhibited higher support for populist candidates.19

To revive rural life thus requires investment in the conditions that strengthen communities and their social cohesiveness. Several policy measures can help, including:

- Supporting community-owned businesses and cooperatives: Case studies from the UK and the European Union show that such community-run enterprises provide important services, help save local enterprises, and foster greater social cohesion, trust, and civic engagement.20

- Investing in digital connectivity: Improving broadband access in rural areas enables residents to maintain social relationships and engage with the broader society, partly mitigating a sense of isolation.21

- Provide funding and assistance for revitalization of downtown areas: A recent study of U.S. rural communities found that revitalizing Main Streets not only spurred local economic recovery but also created more “vibrant, reflective, and cohesive” social environments.22 Evidence also indicates that investments in streetscape improvements, small business support, and inclusive events, such as farmers’ markets and cultural celebrations, draw people to downtown areas and help achieve these goals.

- Investing in so-called third places: Investing in these physical spaces that naturally encourage interaction—hence their name “third places,” as in neither home nor work—means providing funding for building or sustaining community centers, cultural or religious centers, and parks. The goal is to improve opportunities for socializing that underpin societal cohesion.

Investment in rural communities should therefore be an important focus of center-left policymakers. Strengthening these communities will require investment in expanding local economic activity and, crucially, also in creating conditions that facilitate social interactions and strengthen rural civic life. Beyond the economic and social dividends of this approach, it could also help assuage resentments that drive many rural voters to right-wing populism.

Other policy options to counter right-wing populism

The cross-country analysis I and my colleagues performed also confirms the role of anxieties about declines in social status as a driver of populist support in some countries. These anxieties may be partly attributed to concerns about changing demography and the erosion of traditional social roles, but they also could be due to labor market changes and rising employment precarity.

The anxieties about social standing might be addressed through a combination of a targeted industrial policies and active labor market programs designed to create “good jobs” for lower- and middle-class workers.23 Greater emphasis also should be placed on policies that promote a sense of dignity in the workplace. And strengthening workers’ voice through union representation and collective bargaining may help make workers feel that their concerns are heard and addressed by employers and policymakers alike.

Beyond these options, center-left policymakers and politicians should not forget that sentiment does not equate policy. Allaying people’s anxiety about, say, immigration, does not begin and end with putting forth tough and detailed policies regarding entry quotas, visa eligibility criteria, or numbers of border patrol agents.

Speaking to people’s anxieties also requires acknowledging their gravity and selecting candidates that can genuinely express concern—and even anger—about the factors underlying these anxieties and convey a commitment to address them. After all, it is hardly the case that right-wing populist parties have effective solutions to the core problems modern societies currently face; their appeal is much about the sentiment they convey when talking about the problems. Combating populism therefore requires using some of its own effective communication methods.

Conclusion

While grievances stemming from economic dislocation and insecurity contribute to populist support and can be a decisive to the outcome of specific elections, they do not explain why it has garnered such broad appeal across diverse contexts. My research and others suggest that the appeal of right-wing populism is, to a large degree, rooted in culture and identity-based grievances. How center-left policymakers should address these grievances is a question without easy answers, but they should not over-emphasize economic factors simply because it is easier to conceive of a policy remedy for them.

The rise of right-wing populism in the United States and other advanced democracies reflects a profound political shift. To counter this movement effectively, center-left parties must recognize people’s anxieties about issues of identity, social belonging, and cultural change, and focus on policies and messages that speak to these issues in addition to addressing their concerns about rising economic insecurity.

The list of policy solutions provided above is neither exhaustive nor sufficient in itself to counter right-wing populism, but it does sketch out a number of important directions to consider. By crafting an agenda based on solidarity that speaks to voters’ concerns about identity and purpose, in terms of both the policy and the sentiment it conveys, the center-left can chart a more effective path toward countering populism and regaining the trust of the electorate in elections to come.

About the author

Yotam Margalit is the Brian Mulroney Chair in Government at the School of Political Science and International Affairs at Tel Aviv University and a professor in the Department of Political Economy at King’s College London. He has written extensively on the politics of globalization, the rise of populism, and the political repercussions of economic crises.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!

End Notes

1. For example, see Jeet Heer, “Bernie Sanders Is Right: Democrats Have Abandoned the Working Class,“ The Nation, November 11, 2024, available at https://www.thenation.com/article/politics/bernie-sanders-democrats-working-class/; Jason Furman, “The Post-Neoliberal Delusion,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2025, available at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/post-neoliberal-delusion.

2. Yann Algan and others, “The European trust crisis and the rise of populism” (Washington: The Brookings Institution, 2017), available at https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/4_alganetal.pdf; Thor Berger, Chinchih Chen, and Carl B. Frey, “Political machinery: Automation anxiety and the 2016 US presidential election,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 34 (3) (2017): 418–442; Italo Colantone and Piero Stanig, “Global competition and Brexit,” American Political Science Review 112 (2) (2018): 201–218; Christian Dippel, Robert Gold, and Stephan Heblich, “Globalization and its (dis-)content: Trade shocks and voting behavior.” Working Paper 23209 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2015), available at https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w21812/w21812.pdf.

3. David Autor and others, “The China shock: Learning from labor-market adjustment to large changes in trade,” Annual Review of Economics 8 (1) (2016): 205–240; Hedieh Aghelmaleki, Ronald Bachmann, and Joel Stiebale, “The China shock, employment protection, and European jobs,” ILR Review 75 (5) (2022): 1269–1293.

4. David Autor and others, “A note on the effect of rising trade exposure on the 2016 presidential election,” appendix to“Importing Political Polarization? The Electoral Consequences of Rising Trade Exposure,” American Economic Review 110 (10) (2020): 3139–83; Italo Colantone and Piero Stanig, “The trade origins of economic nationalism: Import competition and voting behavior in Western Europe,” American Journal of Political Science 62 (4) (2018): 936–953.

5. Colantone and Stanig, “Global competition and Brexit.”

6. Liugi Guiso and others, “Demand and Supply of Populism.” Working Paper 610 (Bocconi University, Innocenzo Gasparini Institute for Economic Research, 2017).

7. For a more thorough exposition of this argument and evidence, see Yotam Margalit, “Economic insecurity and the causes of populism, reconsidered,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 33 (4) (2019): 152–170.

8. That is assuming that all working-class voters suffer from economic anxiety, and that all those voters would not have voted for the populists otherwise.

9. Yotam Margalit, Shir Raviv, and Omer Solodoch, “The Cultural Origins of Populism,” Journal of Politics 87 (2) (2025), available at https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/732985.

10. Low income is defined as earning less than two-thirds of the median income. See Ibid. for full details on measurement.

11. John Hainmueller and Daniel J. Hopkins, “Public Attitudes Toward Immigration,” Annual Review of Political Science 17 (2014): 225–249.

12. Margalit, Raviv, and Solodoch, “The Cultural Origins of Populism.”

13. Pippa Norris and Robert Inglehart, Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

14. Yotam Margalit and Omer Solodoch, “Against the flow: Differentiating between public opposition to the immigration stock and flow,” British Journal of Political Science 52 (3) (2022): 1055–1075.

15. Joshua L. Kalla and David E. Broockman, “Reducing exclusionary attitudes through interpersonal conversation: Evidence from three field experiments,” American Political Science Review 114 (2) (2020): 410–425.

16. Elizabeth Levy Paluck, Seth A. Green, and Donald P. Green, “The contact hypothesis re-evaluated,” Behavioural Public Policy 3 (2) (2019): 129–158.

17. Henning Finseraas and others, “Trust, ethnic diversity, and personal contact: A field experiment,” Journal of Public Economics 173 (2019): 72–84.

18. Giovanni Facchini, Yotam Margalit, and Hiroyuki Nakata, “Countering public opposition to immigration: The impact of information campaigns,” European Economic Review 141 (2022); Alexander Kustov, In Our Interest: How Democracies Can Make Immigration Popular (New York: Columbia University Press, 2025).

19. Diane Bolet, “Drinking alone: local socio-cultural degradation and radical right support—the case of British pub closures,” Comparative Political Studies 54 (9) (2021): 1653–1692.

20. Nick Bailey, Reinout Kleinhans, and Jessica Lindbergh, “An assessment of community-based social enterprise in three European countries” (London: Power to change, 2018), pp. 1–56.

21. European Commission, “Broadband connectivity stimulates rural revitalization” (2025), available at https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/library/broadband-connectivity-stimulates-rural-revitalisation.

22. Hanna Love and Mike Powe, “Why Main Streets are a key driver of equitable economic recovery in rural America” (Washington: The Brookings Institution, 2020), available at https://www.brookings.edu/articles/why-main-streets-are-a-key-driver-of-equitable-economic-recovery-in-rural-america/.

23. Dani Rodrik and Charles Sabel, “Building a Good Jobs Economy.” Working Paper RWP20-001 (Harvard Kennedy School, 2019).