A new proposal to reform the U.S. estate tax

Over the past few decades, Americans at the top of the income ladder experienced income gains while those further down struggled with stagnant or declining income. But the focus on the rise in income inequality tends to overlook the equally important explosion in wealth inequality. The progressive U.S. income tax system helps reduce the disparities between the highest- and lowest-income families, yet Uncle Sam has little ability to tax wealth.

A new paper by New York University School of Law Professor David Kamin argues that we are missing an opportunity: Kamin contends that it is possible to expand and reform wealth taxes in a way that not only increases government revenue but does so without affecting overall savings rates—an important factor in future economic growth.

The federal government does attempt to tax large sums of wealth if they are transferred via gifts or inheritances. But the estate tax currently exempts the first $10.86 million of a married couple’s estate, or the first $5.43 million of an individual’s estate, and levies a 40 percent tax on the remainder (though the tax collects far less due to key loopholes). That means the estate tax only applies to a tiny slice of the population: Only 0.15 percent of Americans have levels of wealth that exceed that amount, or less than one in 600 among those who died last year.

This rate is historically low relative to prior levels and has a larger exemption, which means it now taxes fewer taxpayers than it used to, and taxes them at a lower rate. The few estates that are subject to the estate tax pay less than one-sixth of their value (about 17 percent) in tax—far less than the 40 percent statutory rate. And even this number is likely to be an overstatement, as there is evidence that these taxes undervalue the size of the estate. Kamin cites one Internal Revenue Service study that finds the internal valuations of estates are about half of what is listed in the annual Forbes 400 rankings. That may be because wealthy estates can afford to game the system by hiring lawyers to employ what Kamin calls “tax planning techniques,” such as perpetual trusts and grantor-retained annuity trusts to pass on their estate without it being subject to a full estate tax.

Kamin proposes two fundamental reforms for federal wealth taxes. First, instead of taxing wealth transfers as an estate tax (which taxes the “donor” of the estate), we should tax the recipient of the inheritance through an inheritance tax. He cites a proposal by Lily Batchelder, also at NYU Law School, which, among other things, would consider the economic status of the individual inheriting the estate. That means that if the estate was divided up between many heirs, there would potentially be a lower tax bill than if the estate were taxed as a whole.

Kamin also proposes a wealth tax that is applied at regular intervals, such as the one that is suggested by Thomas Piketty at the Paris School of Economics and Emmanuel Saez at the University of California-Berkeley. Piketty and Saez argue that combining annual wealth taxes with an inheritance tax can better balance the economic trade-off between equity and efficiency compared to just using the inheritance tax alone. Taxing wealth on a recurring basis also could raise significant revenue: A 1 percent tax on wealth exceeding $20 million would raise $80 billion in 2012 alone. Over ten years, that number would exceed $1 trillion.

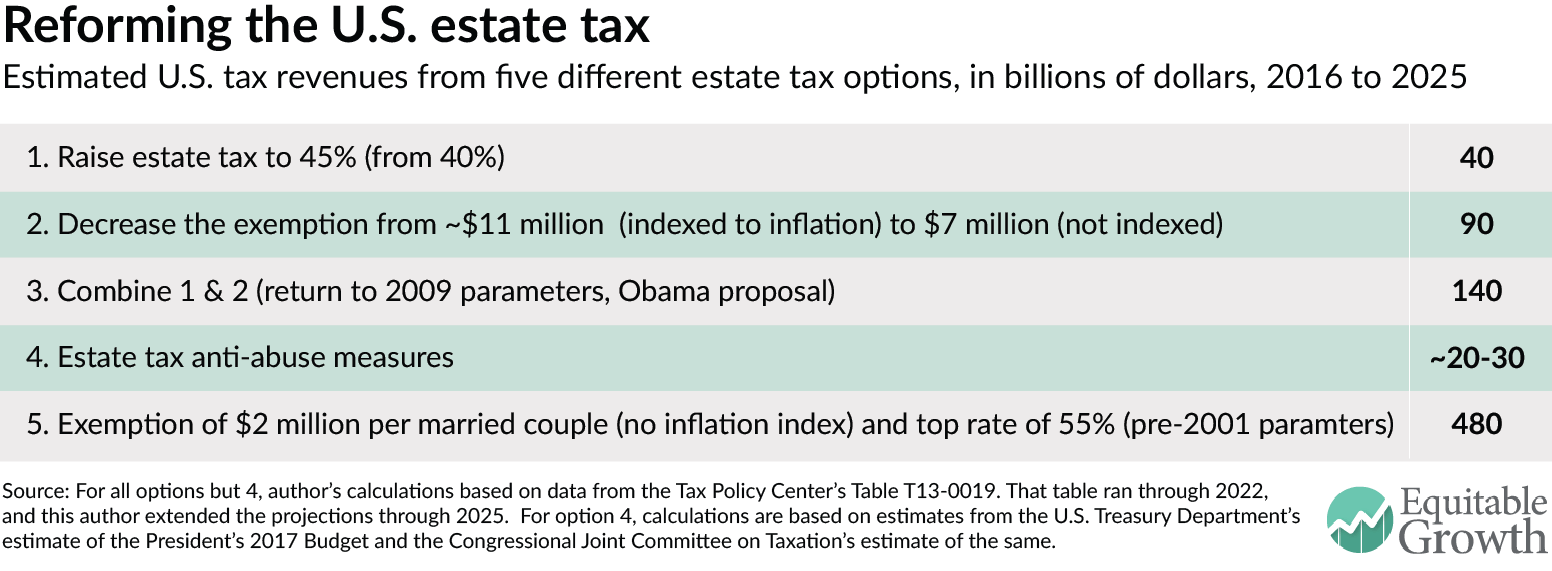

While recurring wealth taxes are not a totally new innovation—11 other wealthy member nations of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development currently use them—Kamin does point out that in the United States, a wealth tax could be subject to legal challenges for constitutional reasons. So in the meantime, he proposes ways to strengthen the estate tax under current law, including closing the loopholes that allow families to bypass taxation. He also suggests that we bring back the estate tax as it was in 2009, with a top rate of 45 percent and an exemption of $7 million per couple. The combination of the two reforms could together raise $160 billion to 170 billion over the next 10 years which, while not as much as a wealth tax, is still significant.

Reforming the way we tax wealth—or at the very least, returning to the way we used to tax wealth—could go a long way in combatting the widening wealth gap, which is currently at roughly the same level as the “Roaring Twenties.” The revenue would also boost public investment in areas that the rich and poor alike benefit from, including defense, the environment, scientific research, and infrastructure. Tax planning will always exist, but as Kamin points out in his paper, “the U.S. tax system can do much better than it does now; the current level of tax planning and distortions is not inevitable—it is a function of a system in need of reform.”