Heather Boushey (and Me) on Thomas Piketty: Tuesday Focus: March 11, 2014

Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century comes out today:

Heather Boushey: Against U.S. Economic Clichés: “Keynes wrote The General Theory… in reaction to… ‘classical economists’… Marx wrote Das Kapital in reaction to the ‘bourgeois economists’… Piketty writes in reaction to the ‘U.S. economists’….

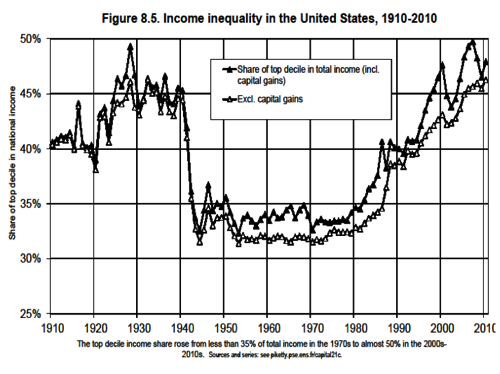

He moved back to Paris at 25, in 1995, because “I did not find the work of U.S. economists very convincing.” Piketty’s method is an explicit critique of academics “too often preoccupied with petty mathematical problems of interest only to themselves.”… The main finding of his investigation is that capital still matters… a recent resurgence… of… capital income relative to national income… to levels last seen before World War I…. Inheritances and income inequality will [probably] keep rising, possibly to levels higher than ever seen…. The data lead Piketty to describe the popular argument that we live in an era where our talents and capabilities matter most as “mindless optimism.”…

Piketty’s evidence suggests it is the rise of what he calls the “supermanager” among the top 1 percent since 1980 that is driving the rise in earnings inequality. It is here that Piketty takes his sharpest swipe at economists. In his discussion of the thriving top decile, he points out that

among the members of these upper income groups are U.S. academic economists, many of whom believe that the economy of the United States is working fairly well and, in particular, that it rewards talent and merit accurately and precisely. This is a very comprehensible human reaction….

It’s easy—and fun—to argue about ideas. It is much more difficult to argue about facts. Facts are what Piketty gives us, while pressing the reader to engage in the journey of sorting through their implications.

If I had to summarize the lessons that I drew from Piketty’s book powerpoint presentation for his Helsinki Lecture, I would say that they are four.

First, that inequality is driven by the dynamics of capital (and more broadly, wealth–wealth includes land and also rent-extraction position as well) accumulation–the capital-to-output ratio and the capital share of income–and by the dynamics of wealth distribution. A society with a high savings rate and a low growth rate will have a high wealth-to-income ratio and a high capital share in income. A society with multiplicative dynamics–in which the return on wealth are such that wealth makes more wealth rather than wealth getting taxed or stolen or bombed or consumed away–will be one with an unequal distribution of what wealth there is. A society with both of those things will be an unequal society.

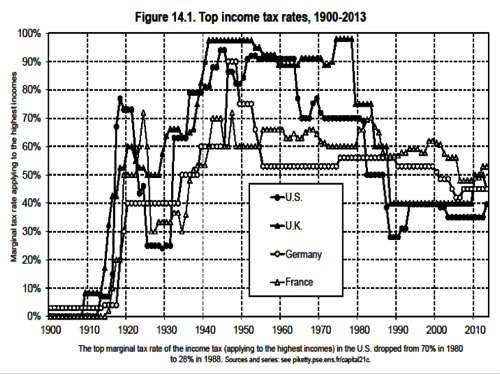

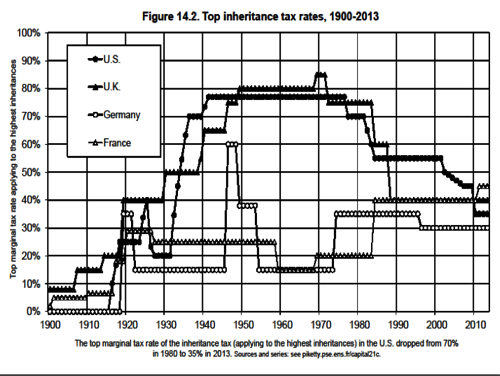

Second, from roughly 1930 to 1980, the North Atlantic had neither of these. Rapid productivity and technology population from the Second Industrial Revolution coupled with the population explosion of the demographic transition era raised the denominator of the wealth-to-income ratio. Wars, progressive taxation to finance wars, the sticking of progressive taxation even after the wars were over, and a popular demand for social democracy and social insurance inhibited multiplicative dynamics by which more was given to those who had.

Third, meritocracy? Make me laugh. In my view meritocracy does not produce inequality. Rather, true equality of opportunity produces relatively small income differentials because there is always somebody almost as good eager to bid for your high-paid job. Inequality emerges either (i) when this generation’s human capital is last generation’s wealth, or (ii) when other non-meritocratic factors are creating jobs that are the equivalent of covering yourself with glue, standing outside at a corner in Canary Wharf, and watching the money stick to you as it blows by.

Fourth, now with the end of the demographic transition era and with the possible slowing of technological progress, we face a world with a much higher capital share of income than over 1930-1980. And multiplicative dynamics are back with a vengeance–largely, I think, because unequal wealth poisons politics and creates a powerful class interested in making sure that multiplicative wealth dynamics persist.

But what does Piketty say?

In his Helsinki lecture, Tomas made six major points:

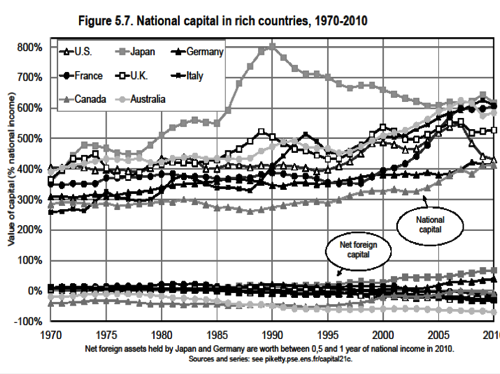

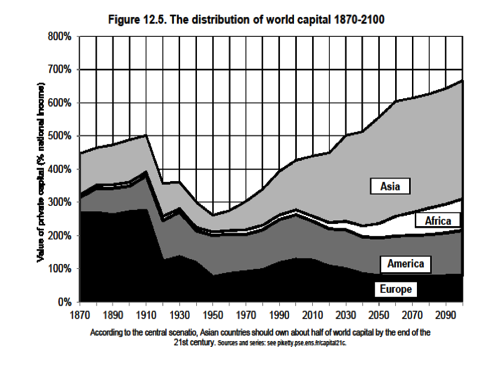

- As growth rates decline in the Old World (Europe and Japan), we will once again see the dominance of capital: a greater proportion of the wealth of society will be held in the form of physical and other non-human-skill assets, and inheritance and position will matter more and individual effort and luck less.

- In fact, given relatively high average rates of return on capital and thus a large gap vis-a-vis the growth rate, wealth concentration is likely to reach and then surpass peak levels seen in previous history as the superrich become those who started wealthy and benefitted from compound interest and luck.

- America remains an exceptional puzzle: it looks, however, like it is headed for an even more extreme distribution of wealth than is the Old World.

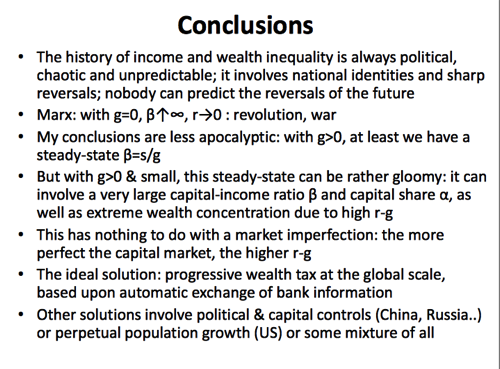

- Remember, however: the evolution of income and wealth distributions is always political, chaotic, unpredictable–and nation-specific: not global market conditions but national identities rule wealth distributions.

- High wealth inequality is not due to any “market failure”: this is a market success: the more frictionless and distortion-free are capital markets, the higher will wealth inequality become.

- The ideal solution? Progressive global-scale wealth taxes.

With that as a guide, let’s jump in…

Europe:

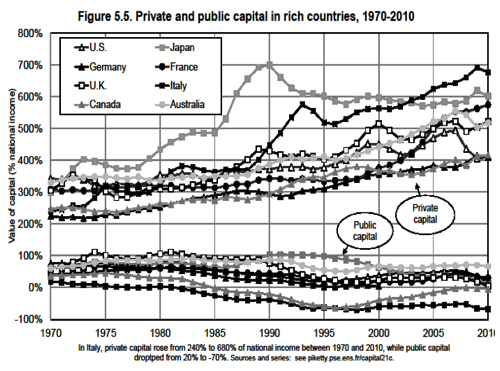

Wealth-to-income ratios are not constant when you look across generations. At such a time frame, the economy’s wealth-to-income ratio is equal to its (a) produced physical capital, plus (b) the value of land and other natural resources, plus (c) value of intangible organizational and idea capital as well.

Piketty says: If all three of these look the same from the perspective of potential savers–and they largely do–then the economy’s wealth-to-income ratio (a different thing than its capital-to-income ratio) will settle at W/Y = s/(n+g), where s is the net savings rate and n and g are the population growth rates and rates of income-per-worker growth, respectively. In a world in which rates of technological progress ultimately driving g and rates of population growth n shift, only if the savings rate s responds sensitively to changes in W/Y at an aggregate level will there be any tendency for W/Y to stay at or near any fixed Kaldor level. And, indeed, in Europe this “Kaldor fact” is not a fact. Piketty stresses that the ratio of wealth-to-income was 6 or so at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, fell in the first half of the twentieth century to 2.5 or so, is now back up to 5, and looks to be heading higher.

And, Piketty says, it is this wealth-to-income ratio that drives inequality. First, although standard growth-economics models assumes that the share of income received by owners of capital, α, is invariant to the capital-income ratio, this is almost surely false. As Piketty stresses, to the extent that rises in wealth-to-income are not due to a change in rent-seeking and rent-extraction, it doesn’t require an economy with a capital-labor substitution elasticity much greater than one for such a large shift in wealth-to-income to produce a large increase in the share of income going to capital.

Second, absent a strict and bizarre theory of inequality of talent, this generation’s inequality in labor income is lat generation’s savings in the form of descendant human capital: labor inequality is lagged capital inequality.

Thus we should not be surprised to note that, throughout Europe, wealth concentration before World War II was extreme. More than 4/5 of wealth was held by the top 10%. More than half of wealth was held by the top 1%. When we calculate the same statistics today, we find numbers a little more than half as great for both of those statistics. And, today, the “middle class” in Europe holds between 1/4 and 1/3 of wealth, compared to 1/10 or less back before World War II.

Why did this shift? Piketty sees two factors:

- The shocks of World Wars I and II–the policies needed to mobilize for victory and the shock of defeat.

- A decline in multiplicative dynamics, in which net savings are correlated with current wealth and the value of r – (n+g) is significantly in excess of 0, where r is in this case not the safe but the averaged realized risky rate of return.

These two factors are, of course, closely related–the wars were enormous disruptions of multiplicative dynamics for both winners and losers, and the question is whether in the absence of such wars the further disruptions of multiplicative dynamics via progressive taxes, social-welfare programs, unions, and the government’s creation of a semblance of equality of opportunity would have happened.

America:

Piketty says: The New World in the 19th century was a land of an enormous amount of productive resources that were low-priced, a land of scarce capital–hence even though the return to capital was high the share of capital in income is low–a land of rapid population growth, and hence a land of opportunity rather than inequality–for white guys in the north: not for African-Americans, and not especiallyfor whit guys in the south.

Piketty says: The late twentieth century has seen the U.S. distribution of income has become more unequal than Europe: America today is now as unequal in income terms as pre-World War I Europe ever was. But in Europe before World War I, inequality was based on possession of wealth. Wealth which carried with it income from capital (land, rent-seeking) and control rights over how that capital (land) was to be used. In America today, income is based on wealth but also, oddly, on position–on control rights over capital, brands, celebrity, and access–and those control rights carry income with them (and may well, as time passes carry wealth as well).

Why owners of capital (and labor) cannot find away around these intermediaries remains unclear to me: Why is a CEO who runs a corporation for a decade able to suck down 20% of its equity value? Why do people pay 2%-and-20% a year to Cliff Asness–and an extra 1% a year to Antonio Scaramucchi to tell them to invest with Cliff Asness? Why do the boards of large private and non-profit bureaucracies pay managers so much in the absence of large, observable differences in skills? The reasons for the non-wealth-based half of U.S. plutocracy remain obscure to me. And I do not think that Piketty manages to shed that much light on them either, which is not his fault–it is a very hard problem. Piketty see the fall in the top marginal tax rate which makes it possible to use your organizational position to bargain for income (rather than merely for internal organizational status and deference) and “the rise of CEO bargaining power” as the most convincing explanations–but it goes a lot further than just CEOs.

Piketty says: sociologically, America today may be the worst of all worlds for those who are neither top income earners nor top wealth successors: you are poor, and depicted as dumb & undeserving: “nobody was trying to depict Ancien Régime inequality as fair”.

Tomas Piketty: Capital in the Twenty-First Century: Powerpoint: