The intellectual history of the minimum wage and overtime

The rapid growth of the “Fight for $15” minimum wage movement and President Barack Obama’s changes to overtime regulations have sparked new rounds of debate over the economic consequences of an increased overtime pay threshold and a higher minimum wage. Advocates of overtime and wage hikes argue these policies protect workers from exploitation and improve job quality. Opponents insist these regulations will hurt workers in the long run, as they will inflict a burden on companies that will be forced to cut jobs. These concerns are nothing new—this debate dates back to the early 20th century, before the minimum wage even existed in the United States and when overtime pay was unheard of.

At the end of the 19th century, economists such as John Bates Clark preached that markets, if left to their own devices, would function at equilibrium levels with the best possible distribution of resources. Rapid industrialization created the Gilded Age of American wealth, and people credited the free market with their increased prosperity. But along with increasing growth, industrialization also sharpened economic inequalities and made certain groups particularly vulnerable to exploitation. Debates over hour and wage limits focused on which groups required labor protections and the best mechanisms for protecting these groups.

Download FileHistory of the Minimum Wage

Read the full PDF in your browser

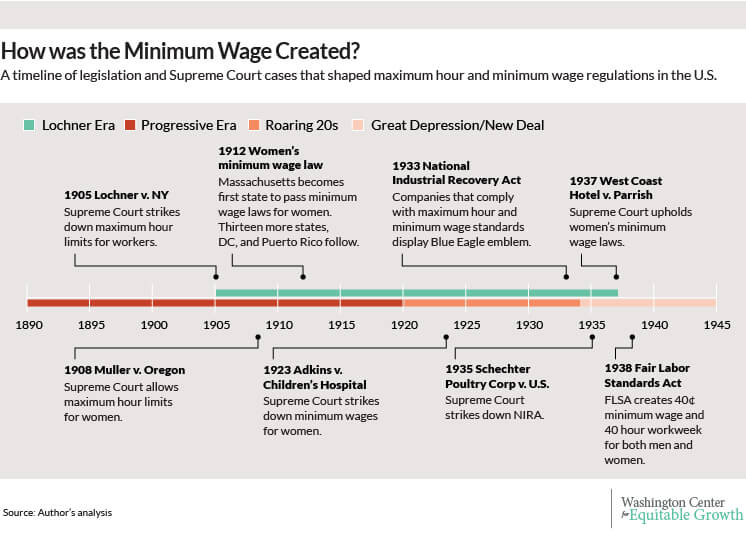

Labor regulations began in the 1890s as state-level maximum hour and minimum wage protections, which the U.S. Supreme Court repeatedly struck down. Federal standards were not created until four decades later, when president Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his Secretary of Labor, Frances Perkins, guided the Federal Labor Standards Act into law. (See Figure 1). This issue brief details the arguments that shaped hour and wage limits in the early 20th century.

Figure 1

Women’s maximum hours

U.S. legal historians usually describe the beginning of the 20th century as the “Lochner Era,” a 32-year period characterized by the Supreme Court’s attempt to protect the free market through its constant repeal of labor laws. The Supreme Court actually was discriminatory in its protection of the free market—although it consistently blocked labor laws that applied to men, the high court allowed restrictions on women’s employment. The Supreme Court passed distinct rulings for men and women by emphasizing different doctrines for the two sexes. For men, the court consistently upheld freedom of contract; for women, the court privileged police powers.

The Supreme Court’s gender discrimination began with cases concerning maximum hour limits. In Lochner v New York (1905), the namesake of the Lochner Era, the court justified its decision to strike down the 1895 Bakeshop Act—which placed hour limits on New York bakers—with the freedom of contract doctrine. Freedom of contract comes from the due process clause of the Constitution, which says that no person shall be “deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” At the time, justices interpreted due process to mean that individuals should be free from restraint except to guarantee the same freedoms to others, and that government could not restrict people’s ability to acquire future property. Limiting the hours that New York bakers worked, proponents argued, took away their liberty to choose the terms of their employment and limited the money they could earn, so maximum hour laws violated freedom of contract.

Just three years later, the Supreme Court set a different standard for women. In Muller v Oregon (1908), it upheld a 1903 Oregon law that prohibited women from working more than 10 hours a day. The court argued that women’s freedom to contract was superseded by the police powers doctrine, which allows government regulation for the purpose of promoting health, safety, morality, and the general welfare of the public. The court found that “as healthy mothers are essential to vigorous offspring, the physical wellbeing of woman is an object of public interest.” In other words, protecting women’s reproductive health was more important than respecting their freedom to contract. Women were also seen as fragile, vulnerable, and lacking the skills necessary to effectively bargain for wages and working conditions, and therefore unable to exercise their freedom of contract. These sex-specific discussions about government-imposed hour limits set the stage for a new conversation: the passage of state minimum wages.

Women’s minimum wages

In 1912, Massachusetts became the first state to pass a minimum wage law that applied only to women and children. Thirteen more states (along with DC and Puerto Rico) followed in the next 11 years. These legislatures passed a patchwork of legislation with a range of wage limits and enforcement mechanisms. States such as Massachusetts created wage commissions to determine industry-specific minimum wages and enforced standards through public shaming, publishing the names of companies that did not comply with the regulations. In contrast, states such as Arkansas set two cross-industry minimum wages for women: experienced women were paid $1.25 a day while inexperienced women only got $1.

The police powers doctrine justified minimum wages for women, but said nothing about how they affected industries. To justify minimum wages on the industry side, academics used the parasitic industries argument. Originally developed by the British economists Beatrice and Sidney Webbs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the parasitic industries argument says that businesses who focused on short-term profit maximization instead of long-term efficiency tend to pay workers unlivable wages. Workers receiving these sweatshop wages become a burden to society, since they have to rely on charity or other family members for subsistence. To fix the problem, companies have to either amend their practices to consider the long-term welfare of the company and the workers, or exit the market.

Women’s minimum wage laws grew out of gender norms supporting women’s protection, but at the same time, racial biases led to laws that neglected women of color. Because minimum wage legislation was usually industry-specific, industries such as domestic work, agriculture, retail, and laundry—all dominated by African American workers—were often excluded from regulation. One case in point: The Wage Board in the District of Columbia set a weekly rate for laundry workers that was $1 lower than the across-the-board minimum adequate weekly wage of $16 it has previously chosen. The board explained that since 90 percent of laundry workers were African American, “the lower rate was due to a crystallization by the conference of the popular belief that it cost colored people less to live than white.” By not extending equal minimum wage protections to African American women, minimum wage laws reinforced their lower economic status.

In the next decade, legal changes in women’s status, paired with the economic optimism of the Roaring Twenties, brought a big shift in minimum wage legislation. Ratified in 1920, the 19th Amendment granted Women’s Suffrage. Shortly after, in a victory for more equal gender standards but a loss for labor protections, the Supreme Court issued a ruling that struck down women’s minimum wage laws across the country. In Adkins v Children’s Hospital (1923), the court overturned the 1918 law that created D.C.’s Wage Board, which had set minimum wages for women employed in laundries and food-serving establishments. Reasoning that women were now politically empowered to advocate for themselves in the free market, the Court privileged freedom of contract over police powers and nullified minimum wage laws in the United States.

This optimism about the competitiveness of the free market did not last long. Once the Great Depression hit, people lost faith in the fairness of the U.S. economy. The failure of the banks cultivated distrust of large corporations. People were afraid that business concentration hurt competition and created unfair trusts. The new popular economic narrative of economists such as Joan Robinson and Edward Chamberlain said that imperfect and monopolistic competition dominated the market. This unfair competition gave businesses a huge advantage, which they used to exploit labor. Public opinion shifted toward seeing government intervention not as redistribution but rather as reestablishing a competitive market.

The Fair Labor Standards Act

In this rapidly shifting political and economic climate Franklin D. Roosevelt won the 1932 elections and appointed Frances Perkins as his Secretary of Labor. With decades of experience advocating for labor rights as a social worker and later as Roosevelt’s Secretary of Labor when the future president was governor of New York, Perkins accepted the federal cabinet office on the condition that Roosevelt would commit to supporting her reform platform, which included hour limits and minimum wages for both women and men. Perkins’ platform originally appeared in the National Industrial Recovery Act, which tried to improve working conditions through voluntary industrial participation. Under the proposed law, industries would be able to form alliances, which previously violated anti-trust laws, if they complied with maximum hour and minimum wage standards. In return, participating companies could display a Blue Eagle emblem in their stores, brandishing their patriotism and commitment to post-Great Depression recovery. In Schechter Poultry Corp. v United States (1935), however, the Supreme Court struck down the law, drawing the ire of Roosevelt and forcing Perkins to find a new way to pass labor reform.

Out of growing frustration with the Supreme Court’s challenges to his policies, Roosevelt came up with a plan to pack the court. He set off a campaign to reform the Supreme Court so he could appoint additional members to the court who would vote in line with his New Deal reforms. Faced with this existential threat and greater public support for labor laws, in 1937 the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Washington state’s minimum wage law for women in West Coast Hotel Co. v Parrish. The court’s ruling de-emphasized the freedom of contract, reversing its 1923 decision and opening the door for future minimum wage legislation.

Following the Supreme Court decision, Perkins and Roosevelt sent a maximum hour and minimum wage bill to Congress. The original draft of the bill had called for industry-specific, regionally variant minimum wages to account for regional differences in prices and cost of living. As the bill made its way through Congress, two more opposition groups emerged: unions and northern industries. Unions feared that government-imposed wage and hour restrictions would undermine their influence in collective bargaining. Northern industries opposed regionally specific wages for fear that industries would follow the cheap labor south. To appease these two groups, Roosevelt and his Democratic allies in Congress tweaked the bill to make it more popular. Roosevelt appeased the unionists’ fears in his State of the Union address by emphasizing that more desirable wages should continue to be the responsibility of collective bargaining. Lawmakers suggested a national minimum wage to satisfy northerners, but set the wage low enough to appease southerners.

In its final form, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 mandated a 44-hour workweek, scheduled to decrease to 40 hours in three years, with time-and-a-half overtime wages. The new law also created a minimum wage of 25 cents an hour, set to increase by 5 cents a year to reach 40 cents an hour by 1945. The original law was not universal. It included exemptions for agricultural, domestic, and some union-covered industries—once again, mostly industries dominated by African Americans. Since the law lacked a mechanism for automatically increasing wages beyond 1945, it has been updated over the decades to increase wages and broaden industry (and racial) coverage. In the most recent revision to the Fair Labor Standards Act in 2009, the federal minimum wage was increased to $7.25 an hour.

Conclusion

The intellectual history of maximum hours and minimum wages is a story of debates over which groups should be protected from exploitation and what form this protection should take. Concerns over women’s health, ambivalence toward African American rights, and advocating for unorganized workers dominated the debate at different points. As social views changed, so did economic policies. Today, women account for two-thirds of minimum wage earners and people of color account for two-fifths. Studying the history of the minimum wage should compel policymakers to question how social priorities influence different groups, who is considered worthy of protection, and to what extent their welfare is considered. By implementing effective maximum hour and minimum wage regulations, policymakers can protect vulnerable workers’ standard of living to encourage productivity, push companies to increase their efficiency, and consequently cultivate long-term equitable growth.

-Oya Aktas is a Summer 2015 intern for the Washington Center for Equitable Growth