Oh Dear: Megan McArdle Relies on John Cochrane, and so Goes Badly Astray…

We find Megan McArdle writing: Why It’s So Hard to Kill Keynesianism:

We all know how stimulus works, right? The government spends money, and then the people who get that money spend it again, which increases gross domestic product and makes us all richer.

The interesting thing about this model is that economists abandoned it more than 30 years ago, as John Cochrane points out:How many Nobel prizes have they given for demolishing the old-Keynesian model? At least Friedman, Lucas, Prescott, Kydland, Sargent and Sims. Since about 1980, if you send a paper with this model to any half respectable journal, they will reject it instantly.

But people love the story. Policy makers love the story. Most of Washington loves the story. Most of Washington policy analysis uses Keynesian models or Keynesian thinking. This is really curious. Our whole policy establishment uses a model that cannot be published in a peer-reviewed journal. Imagine if the climate scientists were telling us to spend a trillion dollars on carbon dioxide mitigation–but they had not been able to publish any of their models in peer-reviewed journals for 35 years.

New Keynesian models do predict stimulative effects from government spending. But they do so through a completely different channel from the old Keynesian models that are still popular with most of the public intellectuals who support stimulus.

What to do? Part of the fashion is to say that all of academic economics is nuts and just abandoned the eternal verities of Keynes 35 years ago, even if nobody ever really did get the foundations right. But they know that such anti-intellectualism is not totally convincing, so it’s also fashionable to use new-Keynesian models as holy water. Something like “well, I didn’t read all the equations, but Woodford’s book sprinkles all the right Lucas-Sargent-Prescott holy water on it and makes this all respectable again.” Cognitive dissonance allows one to make these contradictory arguments simultaneously.

Except new-Keynesian economics does no such thing, as I think this example makes clear. If you want to use new-Keynesian models to defend stimulus, do it forthrightly:

The government should spend money, even if on totally wasted projects, because that will cause inflation, inflation will lower real interest rates, lower real interest rates will induce people to consume today rather than tomorrow, we believe tomorrow’s consumption will revert to trend anyway, so this step will increase demand. We disclaim any income-based “multiplier,” sorry, our new models have no such effect, and we’ll stand up in public and tell any politician who uses this argument that it’s wrong…

I find it interesting that an economic model with zero percent mindshare among professional macroeconomists has nearly 100 percent mindshare among public intellectuals and politicians…

“Where to start?” he asks himself, sitting at a table in the warm 72F Roasterie drinking a $6.89 large mocha with two extra shots and contemplating the 24F temperatures of Kansas City, MO outside…

Would it be by noting that were I to head north on Main St. from here, in the four miles it would take me to reach the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City I would pass eleven check-cashing, car-loan, title-loan, and payday-loan emporia, all of them offering people loans at interest rates of 25%/year or more? There are a huge number of people in this economy who very much look like they are liquidity constrained–and for them it is simply stupid to model their consumption spending as if they were satisfying some intertemporal Euler equation that shifts spending from year to year at a 2%/year real mortgage or BBB bond rate…

Would it be by noting that Milton Friedman’s original Permanent Income Hypothesis thought of “permanent income” as a three- or five-year average of income, not as some infinite-horizon forward-looking optimization exercise? And that whenever I would ask Milton Friedman what he thought the Old Keynesian MPC was, he would say “0.2 or 0.33–but falling as our distribution of income becomes more unequal and as homeownership and thus home equity loan availability expands”?…

Would it be by noting that as Fazzari, Hubbard, and Peterson taught me long ago, principal-agent problems in corporate finance create a very large financial accelerator that makes investment spending depend powerfully on current corporate profits?…

Would it be by noting that Michael Woodford does not think that the government should spend money on totally wasted projects, but instead on useful stuff, that at current government borrowing rates an enormous amount of expanded government expenditures right now pass cost-benefit tests even if you do not include short-term multiplier and long-term hysteresis effects in your model?…

Would it be by noting that Keynes was not really advocating that government should in a Great Depression undertake useless expenditures? That Keynes’s remark that government could improve things by putting banknotes in bottles and burying them in the ground–the passage to which Cochrane is referring when he talks of economists who say “government should spend money, even if on totally wasted projects”–was actually a critique of those (like von Mises) who hoped to see the economy rebalance itself via an expansion of gold mining? That Cochrane has been told that he should read Keynes in context many times, and that he continues to refuse to do so?…

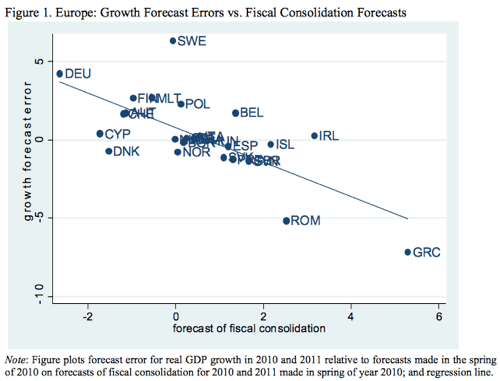

Would it be by noting that Blanchard and Leigh have convinced themselves and many others that in our current policy regime the open-economy multiplier in Europe is about 1.5. And that a multiplier of 1.5 or so in Europe’s very open national economies would go with a multiplier of 2.5 or so in our relatively-closed one?…

Would it be that Cochrane mistakes the logical status of Michael Woodford’s work? That Woodford is marking the metes and bounds: writing that even if we exclude household myopia, liquidity constraints, investment accelerators, and other macroeconomically-significant market failures, playing the microfoundations game straight and building New Keynesian models produces not Classical but Old Keynesian conclusions at the zero nominal lower bound on interest rates?…

Would it be that Cochrane should turn his ire on Robert Lucas, and make fun of Robert Lucas’s business-cycle theory–that unemployment rises in recessions because people (a) think the prices they have to pay are 10% higher than they really are, (b) know that the wages they are being paid haven’t gone up that much, and so (c) quit because they think they are underpaid–instead of picking on poor dead John Maynard?…

But I will do none of those things: I will just ask Megan McArdle to ask a bunch of economists what they think the fiscal multiplier is when interest rates are locked at their zero lower bound, and then write another column both reporting her results and reassessing her belief that a positive multiplier at the ZLB has zero mindshare among professional economists.

1138 words…