Many of the fastest growing jobs in the United States are missing men

Jobs—and quality jobs—are on everyone’s mind. Policymakers on both sides of the aisle are keen to address the economic shifts that wiped out more than 5 million manufacturing jobs since 1990, leaving a growing number of families financially insecure and victim to the country’s growing economic inequality.

But what many policymakers miss is that the growth in services sector has added more jobs than were lost in manufacturing—9 million over the same time period. These jobs are fundamentally different in nature. Manufacturing, for example, boasts a higher proportion of men. But according to a recent report by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research and Oxfam America, many of the occupations that will add the most jobs by 2024, including health care support, administrative assistance, early childhood care and education, and food preparation and services, are comprised of more than 70 percent women. Meanwhile, a growing number of men have stopped looking for work all together. This begs the question: Why aren’t men taking these jobs?

Last week, University of Michigan economist Betsey Stevenson wrote a piece for Bloomberg View arguing that the lack of men in these jobs is due in part to men’s reluctance to embrace traditionally feminine roles. Many of these new services jobs include duties such as cooking, cleaning, and caregiving, which she argues may not exactly appeal to someone concerned with their masculine demeanor. But Stevenson contends that if we care about getting men back to work, we have to make these “women’s” jobs more appealing to men as well.

Yet the lack of appeal of these jobs to many men might not only be because they are “feminine.” The Institute for Women’s Policy Research and Oxfam report identified the 22 fastest-growing, female-dominant occupations and found that they are characterized by low wages, a lack of benefits, and unpredictable schedules. This is the reality for the one quarter of working women employed in one of these professions, all of which pay less than $15 an hour and with few opportunities for advancement. Women of color are overrepresented in these occupations, which means that this pattern contributes to racial inequality as well.

No wonder men aren’t exactly excited about rushing back into a poor-quality job.

It’s notable, however, that not all of these jobs can be characterized as “low-skill.” In fact, workers in these low-wage, female-dominated professions are better educated yet still earn less compared to workers in other low-wage jobs. So why are these female-dominant jobs paid so little if they have become such a critical part of our economy?

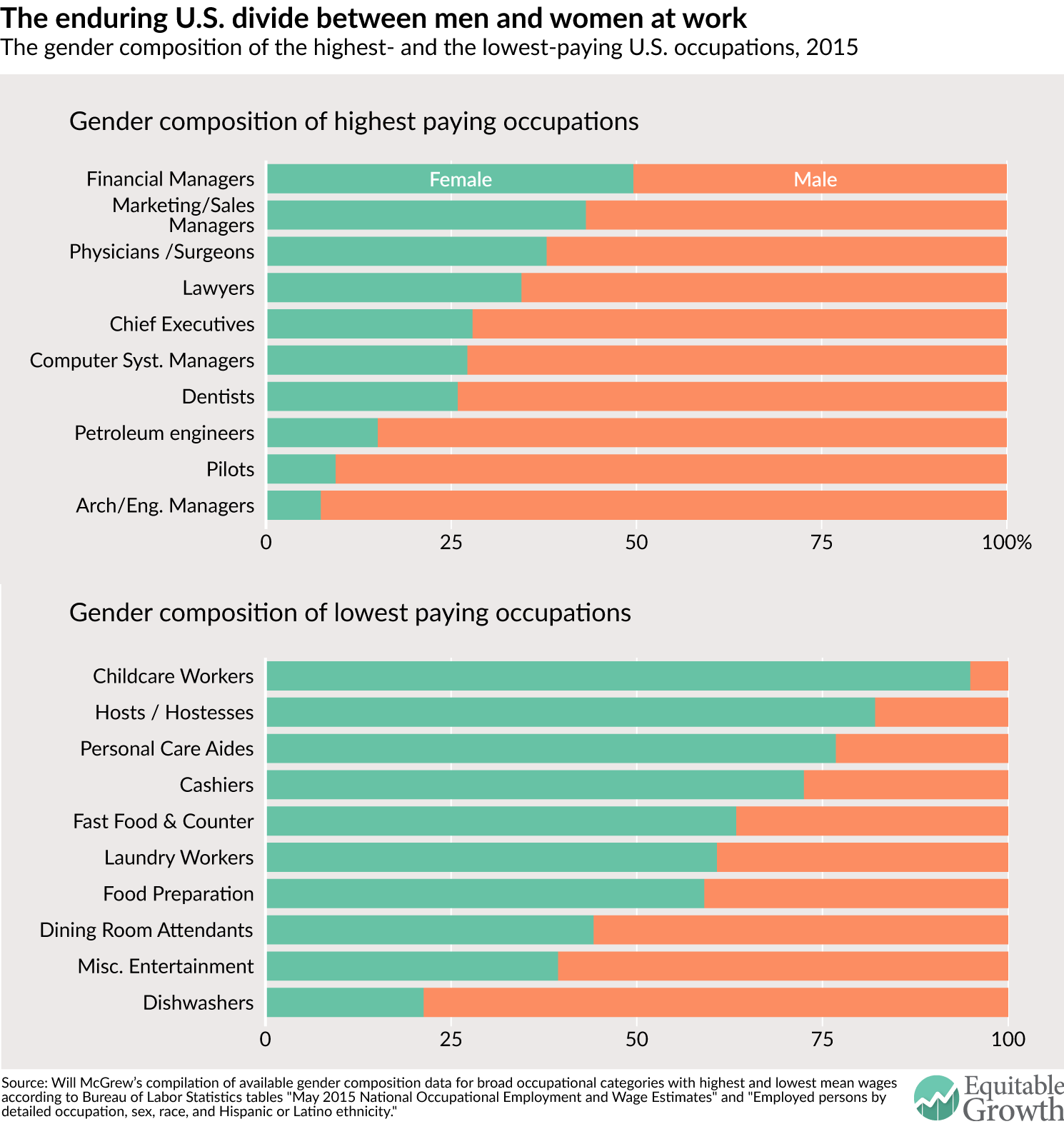

The report suggests these jobs include work, such as caregiving, cleaning, and cooking, that women have historically done for free, and were undervalued once they became paying jobs outside the home. But part of the lack of pay also is because work done by women, whatever it is, isn’t valued as much in the marketplace. A study by Cornell University economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn finds that the difference in jobs that men and women work in is the largest cause of the gender pay gap. Occupations that have more men tend to be better paid regardless of skill or education level. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Just one case in point—last year janitors were paid $142 more per week on average than housekeepers, despite the similar nature of the jobs, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Another study by New York University sociologist Paula England finds that the amount of women in an occupation helps determine whether it is low- or high- paying. As the rate of women working in a given occupation increases, the pay in that occupation (even when controlling for education, skills, race, and geography) declines.

Addressing the way racial and gender inequities can influence job quality is one aspect of promoting these occupations as a jobs for all Americans, not just women. But considering that most families in the United States today rely on women’s earnings, policymakers must start with addressing the working conditions of those already employed in these professions.