Labor Day: Labor standards and institutional support for collective action are essential for an equitable U.S. economy

The landmark U.S. labor laws enacted in the early to mid-20th century continue to represent the main legal structures governing employment relations in the United States. These laws were critical to the advancement of workers for much of the past century, but they weakened over time and must be updated and expanded to create a fair and inclusive economy for workers today and in the future.

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act, encoded private-sector workers’ rights to join and form unions, bargain collectively with their employers, and participate in joint actions such as strikes. A few years later, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 outlawed most forms of child labor, set an hourly minimum wage, and put in place overtime protections to rein in excessive work hours.

These labor laws and protections delivered for most U.S. workers. By banning many anti-union tactics and creating the National Labor Relations Board—the federal agency in charge of enforcing this legislation—the National Labor Relations Act sought to promote “equality of bargaining power” between employers and employees, making it easier for workers to unionize and fight for better working conditions. When passed, both the Fair Labor Standards Act and the Wagner Act excluded many workers of color and many women from their legal protections, reflecting the continuing structural racism and gender biases in the United States, at the time and reverberating still in our economy, despite key amendments to the law since the 1930s.

Still, in the decade that followed the passage of the National Labor Relations Act, the share of workers who were part of a union almost tripled, going from less than 12 percent in 1934 to 35 percent in 1945, and remained higher than 30 percent until the 1960s. Research shows that rising union membership rates, including eventually among workers of color, had a big equalizing effect in reducing income inequality in the middle decades of the 20th century.

Similarly, the Fair Labor Standards Act not only established basic labor rights and protections but also promoted more equitable labor market outcomes, especially after the law was amended in the ensuing decades. Take the 1966 amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act, for example. Ellora Derenoncourt and Claire Montialoux of the University of California, Berkeley found that the introduction of the minimum wage to sectors such as agriculture, restaurants, and hospitals—sectors in which Black workers were overrepresented—explains more than 20 percent of the drop in the Black-White earnings divide during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

That this extension of basic labor rights and protections did not take place until the late 1960s, however, points to the exclusions embedded in much of the New Deal era legislation. By not covering agricultural and domestic workers, both the National Labor Relations Act and the initial Fair Labor Standards Act deliberately left out sectors in which Black workers represented a disproportionate share of the workforce.

Over time, the Fair Labor Standards Act was modified to cover the vast majority of workers. Other legislation in the 1960s also sought to expand workforce protections and rein in discrimination in the U.S. labor market. For instance, the 1964 Civil Rights Act outlawed employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, and national origin, enabling more workers of color to access high-wage occupations and women to increase their labor force participation, narrowing both the gender and racial wage divides.

Yet the main institutions upholding worker’s rights and protections in the United States faced sustained assault over the following decades. A steady and ongoing decline in union membership rates, falling enforcement capacity, and a regulatory framework that struggled to keep up with new forms of employment relationships steadily chipped away at authorities’ and workers’ ability to uphold labor standards.

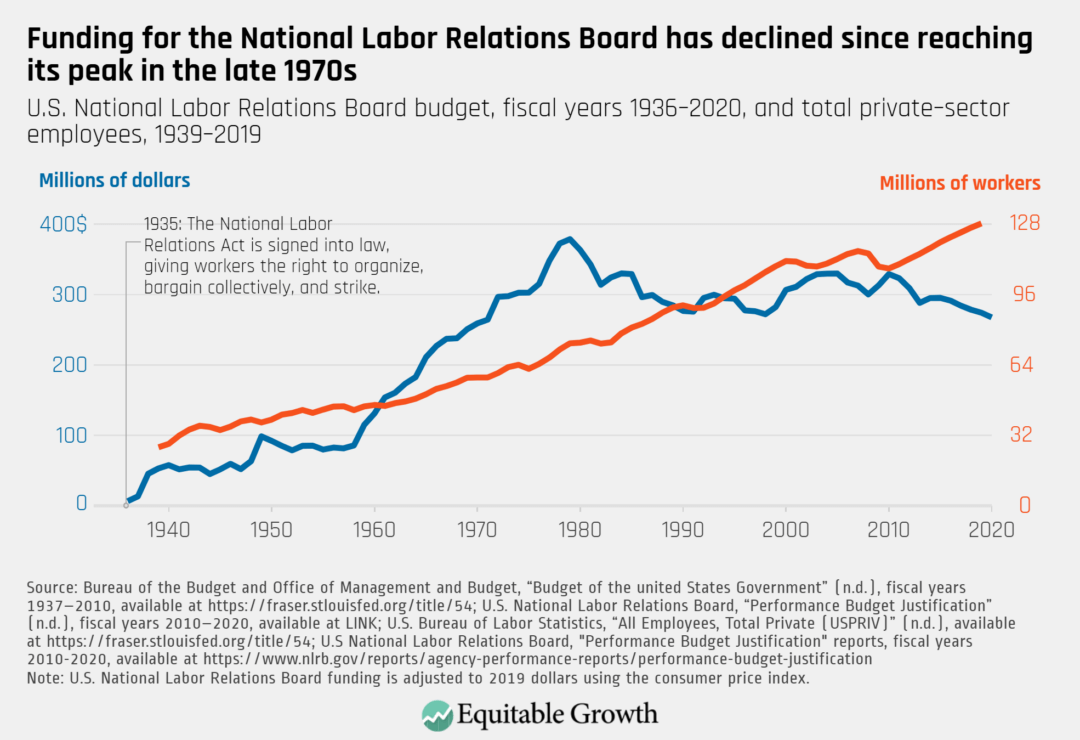

What’s more, federal agencies such as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and the National Labor Relations Board all experienced funding or staffing declines over the past four decades. This fiscal squeeze curtails these agencies’ ability to push back against workplace discrimination, unsafe working conditions, and other workplace abuses even as the number of workers these agencies are supposed to protect grew. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The decline in union density since the early 1960s points to a vicious cycle where, because unions are one of the most effective institutions helping protect workers’ rights, the weakening of organized labor further erodes labor standards. Today, noncompliance with basic labor standards is commonplace and particularly pervasive in low-wage occupations such as child care, repair, sewing and garment work, and housekeeping. For instance, using survey data of the 10 U.S. states with the biggest populations, a recent study shows that about 17 percent of low-wage workers covered by minimum wage protections are paid less than the minimum wage.

When examining changes in U.S. job quality since the late 1970s, David Howell at the New School and Arne Kalleberg at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill show that the share of workers holding low-wage jobs climbed from 39.1 percent in 1979 to 45.2 percent in 2017. This decline in decent jobs—calculated as those that pay at least two-thirds of the full-time mean wage—hit young workers without a college degree particularly hard. Declining job quality in the United States, compared to our peer nations, they write, shows that this decline is not inevitable or the natural result of mismatches in worker skills and employer demand. Instead, they find that policies for improving wages, working conditions, and workers’ bargaining power are key to checking this decline and addressing earnings inequality.

Indeed, institutional support for collective action is critical for job quality, worker power, and equitable economic growth. Independent contractors today do not have access to collective bargaining rights and are not covered by Fair Labor Standards Act protections. Public-sector, agricultural, and domestic workers are still unprotected by the National Labor Relations Act. Even though the demographic composition of these sectors has changed since 1935, exclusions from collective bargaining protections continue to have a disproportionate impact on some of the most vulnerable workers in the U.S. economy. For instance, more than 91 percent of domestic workers are women, 52 percent are workers of color, and 35 percent were born outside of the United States. The Clean Slate for Worker Power project, spearheaded by Sharon Block of Harvard University’s Labor and Worklife Program and Benjamin Sachs of Harvard Law School, puts forth policies that acknowledge how power dynamics shaped and continue to shape U.S. labor law. Among many other recommendations, their agenda proposes extending bargaining rights to sectors and workers not currently covered, regardless of industry or employment status, as well as giving workers a formal role in advising enforcement agencies’ strategies and priorities. Doing so would promote worker power and promote a more fair and inclusive U.S. economy.