Falling behind the rest of the world: Childcare in the United States

We’ve all heard the stories: Mothers who return to work less than two weeks after giving birth. Parents scrimping and saving in order to afford childcare, which now costs more than in-state college tuition or even rent in some places. Workers without sick leave who are forced to forgo pay to take care of a sick child. Such is the reality for millions of families in the United States.

Many policymakers don’t think to address this lack of support for children and working parents, assuming it is an individual responsibility. But once we look at other wealthy countries it’s clear that the United States is alone in this sentiment, spending less than almost all other developed countries.

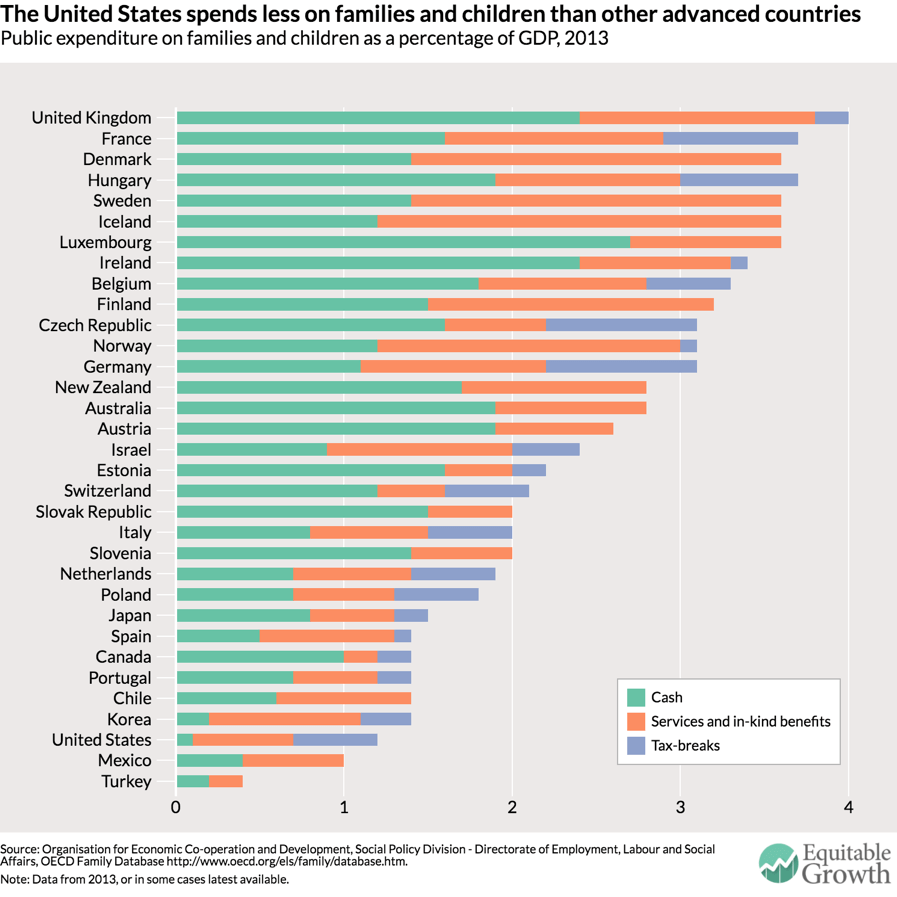

The United States ranks 30th out of 33 member nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in public spending on families and children, which includes policies such as child payments and allowances, parental leave benefits, and childcare support. Within the U.S., most spending comes in the form of services and in-kind benefits as well as tax breaks. In terms of cash benefits, which provides parents the most flexibility in how to provide for their children, the United States ranks last. Forty-two percent of what we spend on childcare benefits is administered through the tax code, a more complicated and less efficient form of benefit delivery. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

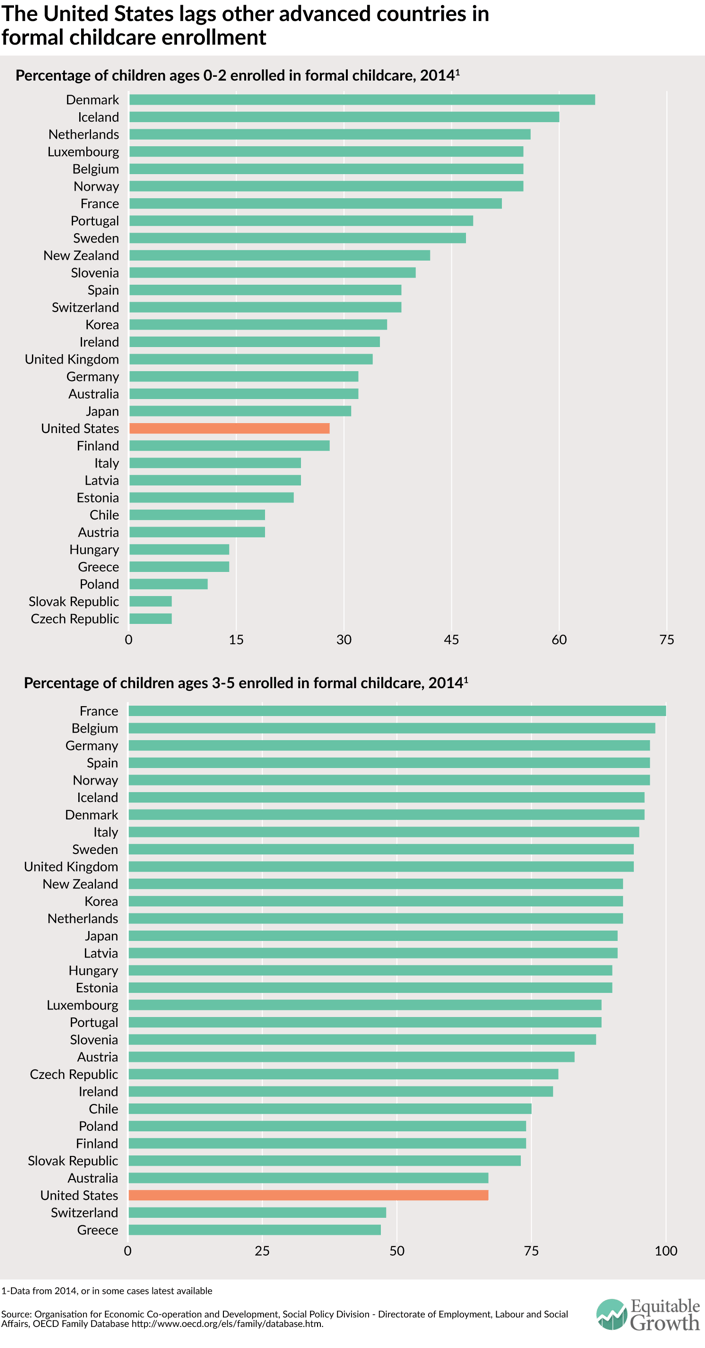

As for childcare, the United States ranks 20th out of 31 OECD countries (for which we have data) in percentage of children ages 0-2 who are enrolled in formal childcare and 29th out of 31 countries in percentage of children ages 3-5 who are enrolled in formal childcare. Only 28 percent of children ages 0-2 in the United States are enrolled in formal care, far behind most other advanced economies. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

The stark differences between childcare enrollments the United States and most other OECD nations comes down to policy differences. Most European countries invest heavily in high-quality education-based care and prekindergarten programs that serve all children. In contrast, the United States largely targets low-income families through programs that are subsets of larger policy initiatives and exist in three separate administrative structures: Head Start, Pre-K programs, and childcare vouchers for families with earnings less than 200 percent of the federal poverty line (funded through the Child Care and Development Block Grant and Temporary Assistance for Needy Family programs). And while middle- and professional-class families do have access to the Child Tax Credit, it is insufficient to meet the needs of most families considering the current cost.

The quality of U.S. early care and learning programs also is much lower than their European counterparts. And a significant amount of children who are eligible for assistance never receive it because of long waiting lists a lack of availability. A report put out by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services finds that only 17 percent of children eligible for subsidies through the Child Care and Development Fund and other related federal programs received them.

Recent research shows the promise and tragedy of childcare in the United States. Not only is prohibitively expensive, it is one of the most effective policy interventions for children, families, and the economy. Investing in high-quality childhood care and education programs has been shown to be one of the best ways to improve individual outcomes for children and reduce inequality overall. It also keeps parents in the labor force—particularly new mothers—and promotes equal pay among men and women over the lifecycle of their careers, which means that families have more income. These factors, along with the substantial long-run returns on investment in early childhood programs, mean that while our own kids will always be an individual responsibility, their well-being should also be re-framed as a national economic and social priority.