The consequences of higher labor standards in full service restaurants: A comparative case study of San Francisco and the Research Triangle in North Carolina

Overview

Across the United States, policymakers in states and cities are grappling with a groundswell of public support for higher local minimum wages as well as other improvements in labor standards, among them better health care and paid sick leave for employees. In many of these communities the so-called “Fight for $15” movement, led predominantly by fast-food restaurant workers seeking to raise local minimum wages to that level, is spurring policymakers to consider the economic merits and possible adverse effects of such a policy move.

Download Fileinside-monopsony-ib Download this Issue Brief

Overall, most economists agree that moderate increases in the minimum wage do not result in job losses. In fact, boosting the minimum wage may reduce employee turnover—a net positive result for employers who could spend less on hiring and training new workers and enjoy sustained productivity from their employees. Yet economists are less sure how locally-enacted minimum-wage raises and higher labor standards reshape employment practices within individual companies. One way to find out is to compare one community where higher labor standards are in place with one where there are no enhanced standards, focusing on one industry in particular.

Such a comparison is particularly apt in the full service restaurant industry in San Francisco and the Research Triangle communities in and around the cities of Durham, Raleigh, and Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Local labor standards in San Francisco include the nation’s highest minimum wage, a mandate for employee health care, and paid sick leave. In contrast, full service restaurants in Research Triangle communities follow lower federal minimum wage guidelines, including much lower hourly wages for tipped employees ($2.13 per hour), and are not required to provide employee health care or paid sick leave.

This issue brief details the findings of a comprehensive research paper that I presented at the Labor and Employment Relations Association Conference in January of this year. I examine employer responses to higher labor standards through a qualitative case comparison of the full service restaurant industry across these two fundamentally different institutional settings. The results are striking.

In San Francisco, higher labor standards led to greater “wage compression” in specific occupations within the restaurant industry, meaning that employers had less “wiggle room” to offer slightly higher wages to cooks or dishwashers or food servers or bartenders. Concurrent with this wage compression was a rise in professional standards as employers sought to hire and keep already well-trained workers at higher wages and with expanded benefits. Both developments reduced turnover and attracted more professional employees who maintain a high level of customer service.

In the Research Triangle region, the lack of higher labor standards led to a wider distribution of wages across the industry and within individual establishments. Thus employers could differentiate wage levels within job categories to a greater degree. This allows a labor practice that offers low-wages for entry-level employees with little experience but accepts a high rate of turnover as a result. This practice also translates into higher training expenditures for firms. In San Francisco, employers required more experience and professionalism from their new hires.

In both cities, however, a large wage gap remains between front-of-house and back-of-house occupations—a gap that correlates strongly with existing racial and ethnic divisions within restaurants (Latinos in the back; whites in the front). Some employers in San Francisco are addressing this gap by radically restructuring their compensation practices by adding service charges and, in some cases, eliminating tipping. In these restaurants, wages are more balanced across workers, whether they are making food in the kitchen or taking the orders and serving food and drinks to customers.

These findings are important for state and local policymakers to consider. Full service restaurants in the United States added 811,700 jobs nationally between the end of the Great Recession and October 2015, outpacing overall private-sector job growth by nearly 7 percent. What’s more, this trend is expected to continue as jobs in food service occupations are projected to grow faster than the overall labor market through 2030. Thus the restaurant sector is a useful harbinger for the predominant labor market conditions that policymakers can expect going forward—namely the proliferation of low-wage jobs in service industries that can’t be offshored.

Understanding how labor standards affect the pace of job creation and more general aspects of the employment is critical. In the full service restaurant industry in San Francisco, higher labor standards suggest the following results may occur in other cities enacting similar policies:

- Higher professional standards may result in lower employee turnover and more productive workers.

- Lower employee turnover and more productive workers may increase sales for owners and ultimately create better dining experiences for customers through better service.

- Higher professional standards may limit entry-level opportunities within the industry, while lower standards may result in more employer-provided training for new workers.

- Currently large wage gaps based on race and ethnicity between restaurant workers in the kitchen and servers and bartenders interacting directly with customers are not fully resolved by higher labor standards.

- Steps to end tipping in favor of salaried employees in the front and back of restaurants may result in more uniform wages within restaurants, and may result in less ethnic and racial inequality within individual restaurants.

There are, of course, limitations in how much local labor standards can improve the quality of jobs within the restaurant industry. More research is needed to fully assess the impact on overall wage inequality and opportunity structures more generally. But broadly, my research suggests that “high-road” labor standards may well lift wages overall while reducing wage inequality and improving professionalism.

The full service restaurant industry today

The restaurant industry employs more than 10.2 million workers today, of which about 5.3 million are employed in full service restaurants, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The restaurant industry overall epitomizes two trends evident in service industries overall in the United States—relatively high growth alongside low job quality—which is arguably why the sector is facing new demands for minimum wage increases at state and local levels.

The U.S. economy is slowly recovering from the depths of the Great Recession, yet the labor market continues to show weakness even as the unemployment rate has fallen to a below 5 percent. Despite optimistic accounts of the “re-shoring” of manufacturing and a recovering housing market, economic inequality is on the rise. That’s because the majority of jobs created since the end of the recession are relatively low-wage. Indeed, a unique feature of the current recovery is the so called “missing middle” in the pattern of job growth, with relatively few new middle-income positions or career pathways for workers who lack advanced skills. As a result, an increasing number of workers remain in low-wage positions for longer periods of time. Jobs that were once viewed as “stepping-stone” positions, among them restaurant work, are increasingly becoming relatively permanent careers that have little opportunity for long-term wage growth.

Recent research conducted by Restaurant Opportunity Centers United and affiliated scholars provides new evidence on wages, benefits, working conditions, and the extent of racial and ethnic discrimination. In 2011, the organization released a study conducted in eight large metropolitan regions that consisted of surveys and interviews with both employees and employers that documented the prevalence of low wages, lack of access to health benefits and sick leave, and persistent occupational segmentation by race.

More recently, scholars Rosmary Batt and Jae Eun Lee of Cornell University and Tashlin Lakhani of Ohio State University presented results based on a national employer survey across 33 large metropolitan areas focused on variation in human resource practices across restaurant market segments. They find a clear link between higher quality human resource practices and lower turnover. In a related study Batt highlights case studies of restaurants that pursued what she calls “high-road” practices, which include higher relative wages, more full-time work, and more investment in training—all of which resulted in lower employee turnover and improved productivity.

Conditions in the low-wage service sector overall are at a historically low level, with stagnant wages, uncertain working conditions and hours, and a hostile regulatory environment toward organized labor. Given these trends, a central concern for policymakers is what can be done to reduce wage inequality in these growth industries of the future. The impact of publicly mandated labor standards on employment and employee benefits is well studied and continues to be debated among economists and policy makers. But there are important missing pieces in our understanding of how locally enacted labor laws may have deeper consequences. In many ways, the behavior of actual firms remains a “black box” for researchers in the field. Raising labor standard has an affect beyond just the level of, among them changes in the rate of turnover, productivity, training, tenure, and professional expectations and norms.

A tale of full service restaurants in two cities

Using a methods-comparative case design that analyzes employment practices across the restaurant industries in two institutionally divergent urban labor markets—San Francisco, which has the nation’s strongest local labor standards, and North Carolina’s Research Triangle region, which does not—one can discern how higher labor standards affect wages and professionalism in the full service restaurant industry. (See the brief methodology at the end of this issue brief or the LERA website for a link to the full research paper.)

San Francisco employers must pay the nation’s highest minimum wage ($10.74 per hour rising to $15 by 2018), a pay-or-play health care mandate (up to $2.33 per hour) in which either the employer or the city provide employee health insurance, and paid sick leave requirements. In addition, tipped workers must be paid the full minimum wage. In the Research Triangle region of North Carolina there are no locally enacted labor standards. Thus, the effective wage in San Francisco is more than $13.00 per hour. North Carolina, in comparison, follows the federal standards of a $7.25 minimum wage and $2.13 tipped minimum wage, and has no paid sick leave or health care spending mandate.

While the regional labor markets of these two cases differ on a number of dimensions beyond the strength of local labor standards, there are a number of similarities that make this comparison plausible for detecting causal effects of labor standards. First, both regions are home to many high-tech employers and both have comparably tight overall labor markets. Lastly, both cases have a similar number of full service restaurant establishments, resulting in a similarly sized sampling universe.

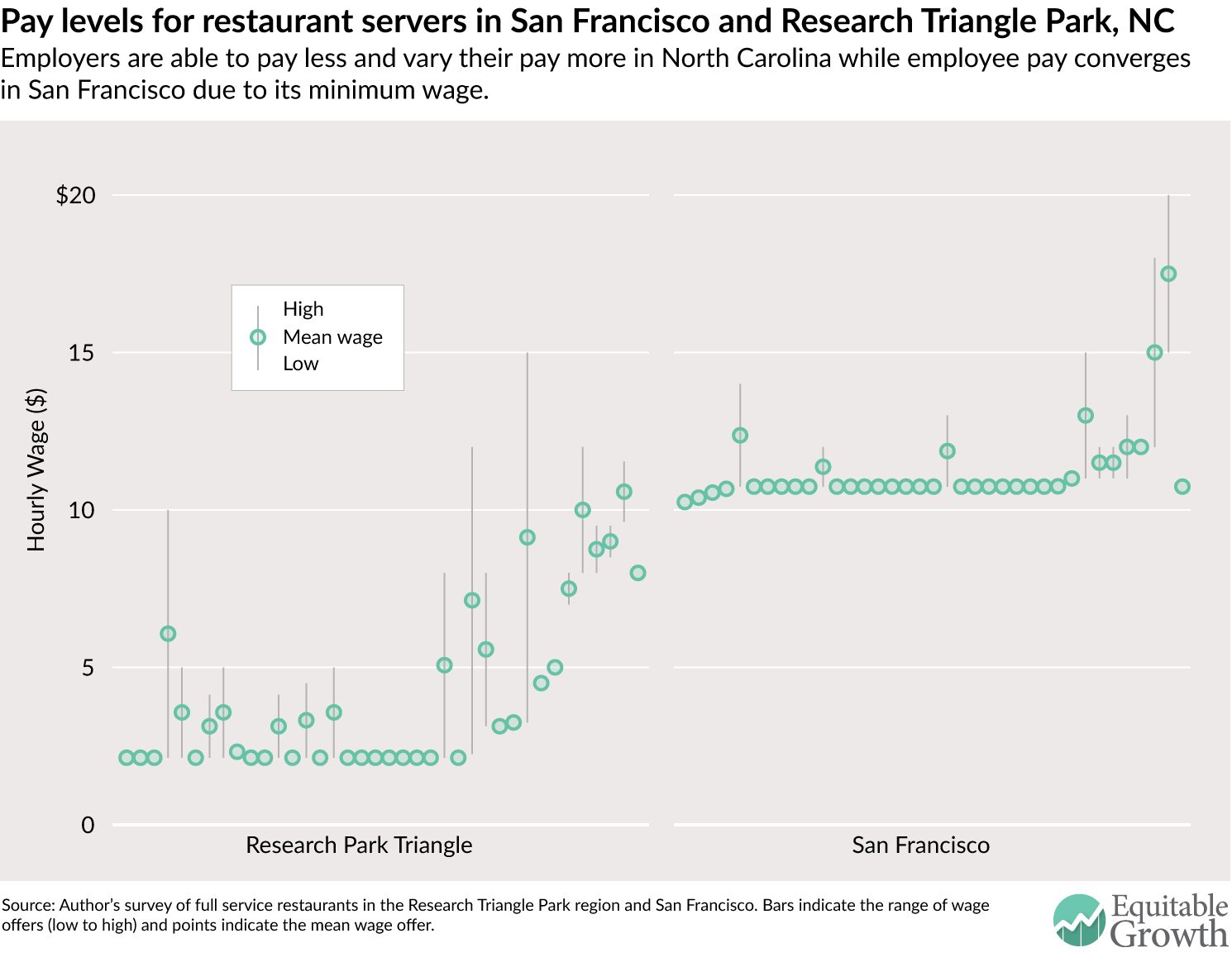

The first finding in my research is perhaps the most telling—San Francisco’s higher minimum wage compared to North Carolina means that the San Francisco restaurants experience less variation in existing wages in different occupations within their establishments and among the establishments themselves. In other words, San Francisco experiences a general convergence of “high road” employer practices compared to the Research Triangle region’s existing “low-road” employer practices. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

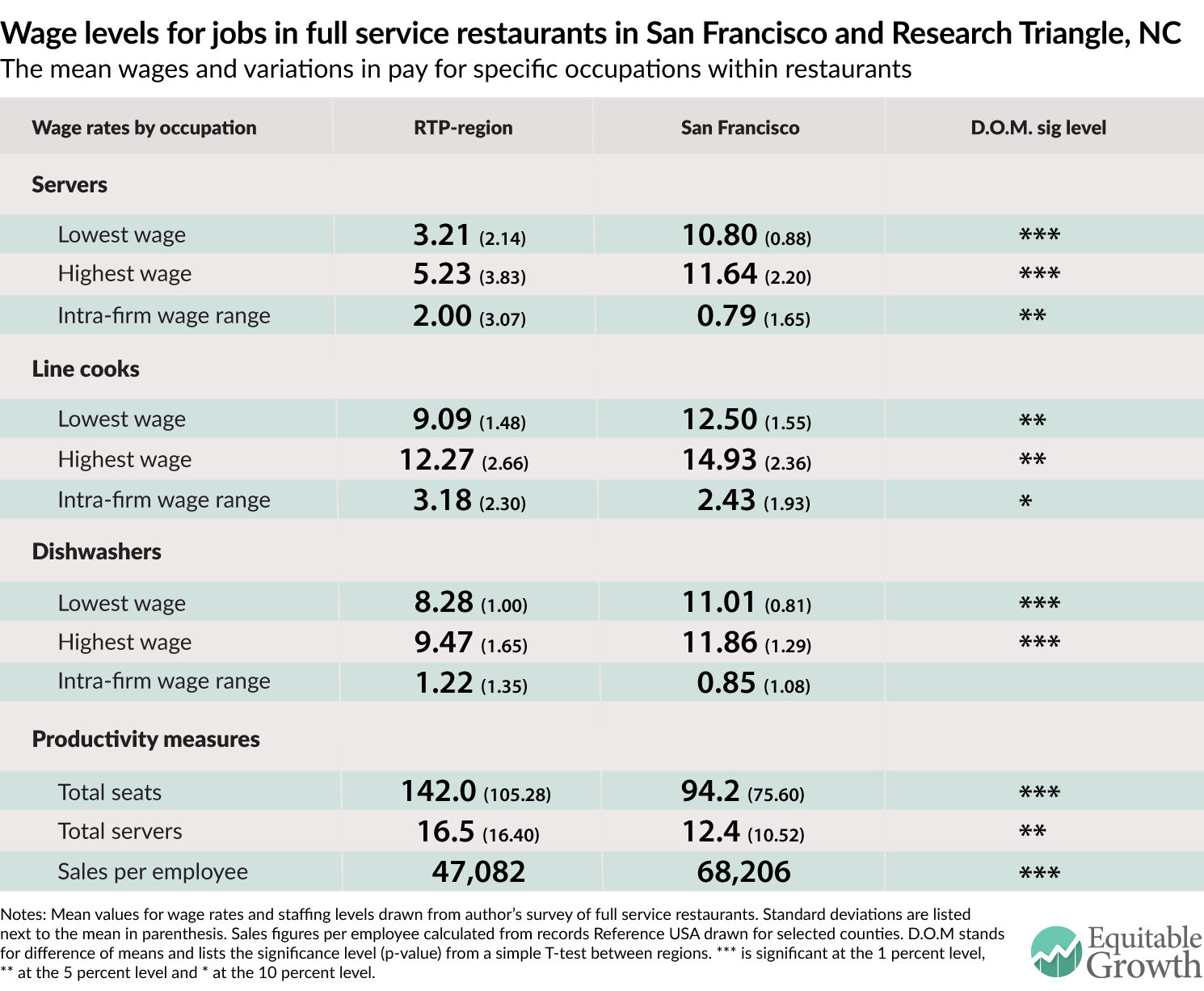

The same pattern is apparent in other jobs within these restaurants in the two cities. Overall, the variation in wages is greater and the wages lower in the Research Triangle region North Carolina compared to San Francisco. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Pushing the High Road Higher in San Francisco

My research also finds that other non-pay related labor standards also had an effect on restaurant labor practices. This is particularly evident in how some employers reacted to the enactment of San Francisco’s pay-or-play health care mandate. Rather than requiring employers to provide insurance directly to workers, the San Francisco Healthy Families Act of 2007 requires employers to pay up to $2.33 per hour worked for each employee. These payments can go either directly to the county health system—where resident workers can receive low-cost care—or into a separate health care spending account set up for each worker. This mandate involves a significant but uniform cost increase for all employers in the industry.

After the passage of this law, some employers decided to spend more than the mandated minimum for their employees’ health insurance in order to provide actual employer-subsidized health insurance to all workers—a benefit that is extremely rare in the industry. As one employer said: “This year for example, we did employee health insurance for everyone…now everyone has real insurance, not just the city thing. We think and hope it will help retain employees.”

Another San Francisco employer echoed the logic of providing full employer-sponsored health insurance rather than simply paying the lower cost option of a per-hour fee to the City. The manager of one neighborhood-based fine dining restaurant explained: “Part of our decision to offer health care goes beyond a simple cost-benefit. What’s another thousand dollars if you already have to spend a certain amount of money. There is a kind of revolutionary like revolt thing happening in that I’m not going to just sign a check over to the city. I’m going to actually give it to my employees. And then the other part is it becomes part of your hiring and your attraction is that you say hey, we offer full benefits.”

This manager’s initial sentiment reflects animosity toward the city government for enacting the Healthy Families law in the first place. Yet the employer’s actual behavior in paying more for full insurance indicates how the labor standard induced the employer to go above the minimum and embrace the potential retention and morale benefits for their workforce.

Beyond direct wage and benefit offers, employers in San Francisco reshaped other aspects of their employment relationship in an effort to differentiate themselves from other employers in the market, and to ultimately retain valued employees. Several interview subjects discussed how they attempted to create a unique work “culture” that is “exciting,” “fun,” or offers indirect benefits to workers, even in cases where employers cannot raise wages beyond the mandated level. One case in point: An owner-manager of a casual neighborhood restaurant allows line cooks to use the resources of the restaurant to further their career development and pursue income-generating work as part-time caterers. Another employer tries to retain key workers in lower-paid occupations through the use of in-kind compensation that is matched to the specific needs of the individual worker—in this case an employee-of-the-month award for back-of-the-house employees in the form of calling cards to reach families back in Mexico.

While these may seem like relatively minor gestures on the part of some employers, these forms of non-wage compensation represent additional ways in which employers try to differentiate themselves in order to retain workers. In the face of strong, binding labor standards that effectively limit the degree to which they can vary wage levels (“taking away the low-road”), employers try to structure their relationship with their workers in other ways. In these two examples we observe restauranteurs who—perhaps implicitly—are adopting some of the same progressive human resource practices typically associated only within high-skill industries or occupations. Specifically, they are recognizing and seeking to accommodate the individual needs of each worker, whether that relates to the worker’s need for outside income through catering or in-kind support of family obligations.

Worker training, retention, and productivity in the two cities

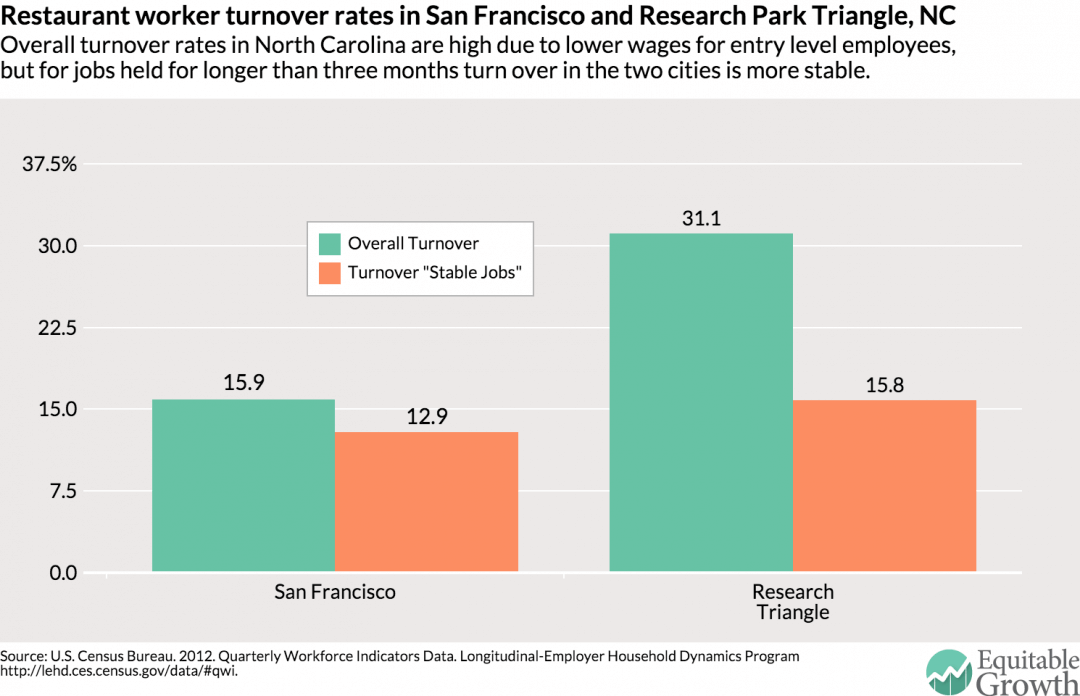

One reason employers need to do worker training in the San Francisco restaurant industry compared to the Research Triangle region is to retain workers. More stable jobs are definitely more in evidence in the city. The rate of turnover for the overall full service restaurant industry in San Francisco was 15.9 percent in 2012, according to official statistics from the Quarterly Workforce Indicators program. This compares to 31.1 percent in the Research Triangle region.

Importantly, however, this stark contrast in turnover is largely due to the relatively high rate of short-term workers who enter and exit employment at a given firm within the same quarter in the two cities. The difference in the turnover rate for “stable” jobs—meaning jobs that last more than one quarter—is much lower (12.9 percent versus 15.8 percent. This means that the full service restaurant sector in the Research Triangle region features a significantly higher number of unsuccessful, or weaker job matches than San Francisco’s restaurant sector. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Those very short term jobs—lasting less than one quarter—are often described by labor economists and other observers as evidence of bad matches between employees and employers. Such high turnover is because workers quit to take a better job, stop working altogether, or were fired. But such high turnover is also indicative of employers operating in labor markets with lower standards hiring workers with weaker expectations of worker quality, which leads to a lower bar for entry level jobs and ultimately more firing of low-quality workers.

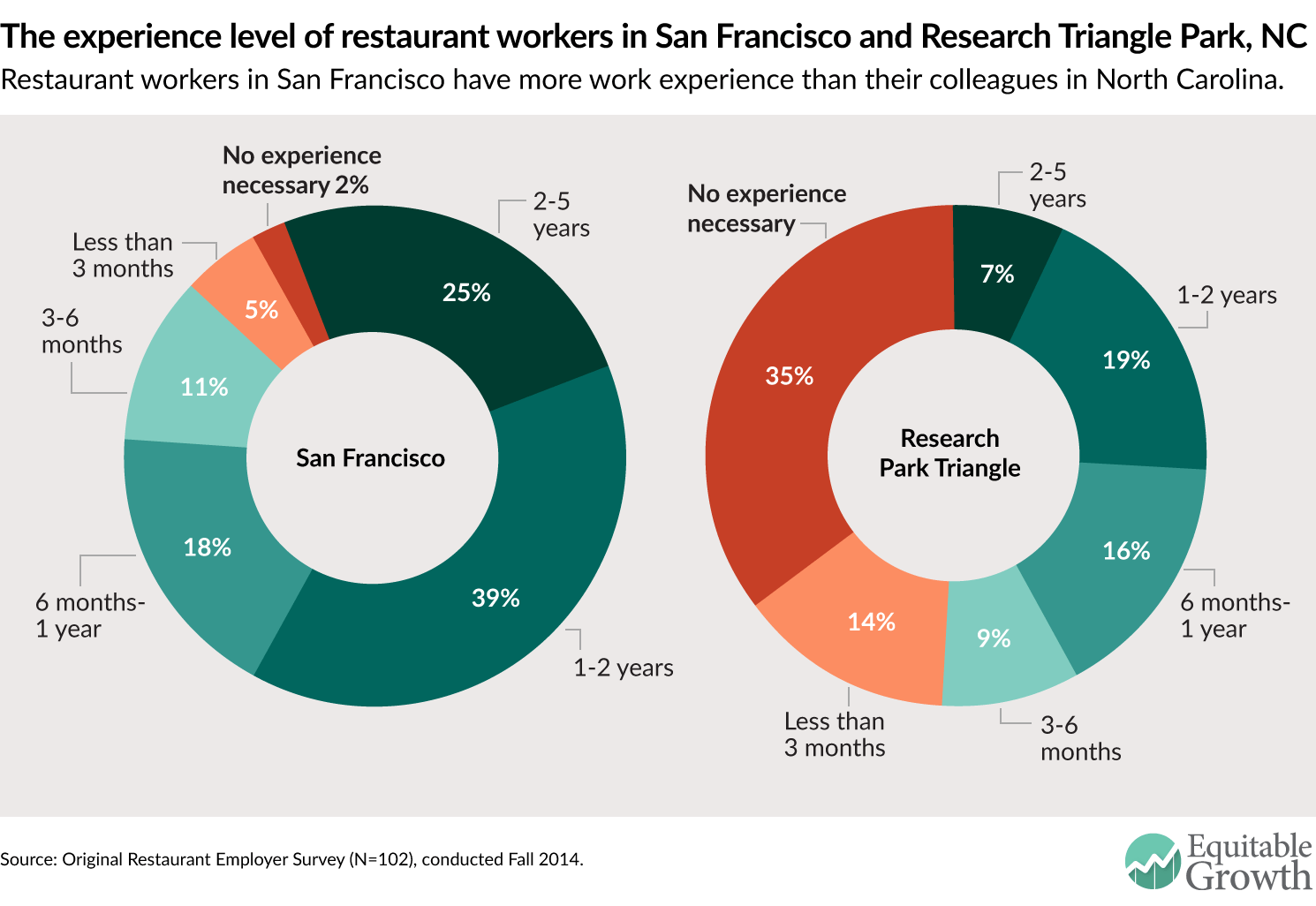

Such differing expectations are evident in the age and education of restaurant workers in in these two cities. The restaurant industry in the Research Triangle region tends to hire younger workers with a lower level of formal education. Specifically, 49.5 percent of workers in there are under age 24 or have less than a high school education, compared to 38.9 percent in San Francisco. Conversely, 40.6 percent of workers in San Francisco have some college or a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 29.7 percent in the Research Triangle Region. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

In addition to hiring an older and more educated workforce, San Francisco employers generally engage in more careful searches, which lead to overall better matches. First, employers in San Francisco report higher experience requirements for new hires across the occupational spectrum. As seen in Figure 4, only 8 percent of survey respondents in San Francisco reported that new servers could be hired without any previous experience in the restaurant industry, compared to 46 percent in the Research Triangle region. Also, a larger proportion of the San Francisco employers reported experience requirements of over one year—33 percent in San Francisco, compared to 25 percent in North Carolina.

The lower bar for entry into employment is also confirmed in employer interviews. One manager of a neighborhood bistro in Raleigh explained what he looks for in a new front-of-house worker: “Basically, we require [that a server] can work a four-shift minimum per week and go an entire shift, an entire eight-hour shift without smoking a cigarette and [without] any facial piercings or anything. Beyond that, just come in with a smile on your face.”

Even at restaurants in the region that do prefer experienced workers, managers and owners did not articulate how experience matters or which specific skills and industry-specific knowledge they require. As one upscale bar-and-grill manager explained: “We look for at least one year’s experience, but the biggest thing we look for is we look for the person. We don’t look for the skill. I could teach anybody how [to] wait tables [and] pour drinks. I can teach anybody how to cook steaks. What I can’t teach is how to be a good person.”

Employers in San Francisco discussed the minimum level of experience needed to work in front-of-house positions in a distinctly different tone. Rather than viewing servers as essentially interchangeable laborers who can be trained quickly and easily if they possess a modicum of personal hygiene and a friendly personality, employers in San Francisco exhibited a clear description of what a “professional server” was. One mid-scale restaurant employer said of her front-of-house staff: “We have a lot of people who have made it a career and they’re investing in the knowledge of the product and learning their trade or already know their trade because they’ve done it for years.”

Another San Francisco neighborhood bistro owner described the level and nature of experience needed to fill a server position at his restaurant. “Realistically, to work here, I would say [a server needs] five years of experience, because there’s a wine knowledge level that I expect that you really just couldn’t get any other way,” he said. “If you have ten years of experience at Applebee’s, that doesn’t do anything for me.”

Ultimately these responses indicate that employers in San Francisco are looking carefully at each candidates’ resume and approaching the hiring process with a set of expectations about the nature of work, the skills (how to manage a customer’s dining experience rather than just take orders), and industry-specific knowledge needed to perform at a high level. San Francisco employers tend to view their employees—front-of-house more so than back-of-house—as professionals rather than basic labor inputs.

This rise of professional norms—or the exhibited expectations of employers for certain worker traits that are typically associated with highly trained professionals—can also be seen in the unexpected finding on employer-provided training. Some labor market economists argue that “high-road” employers will spend more resources on training while “low-road” employers expect their low-wage workers to quit and because their low-wage workers seem easily replaceable. But at least in the full service restaurant industry just the opposite is true. San Francisco employers reported spending less time offering formal training periods for both front-of-house and back-of-house staff. Instead, they seek out and expect to find workers who already possess a high level of skills in the industry.

In contrast, more employers in the Research Triangle region discussed a recruitment and training model that was more likely to involve formal screening mechanisms for a high volume of applications and a longer, more formal training period for new hires (particularly for front-of-house workers). These training strategies are maintained to deal with the high level of labor turnover and the reliance on relatively less-skilled workers. The manager of a large sports bar-and-grill described the recruitment and training process at his establishment as highly scripted. “We do all of our applications online,” he said. “When people come in, we don’t physically hand them a piece of paper. We hand them a card. It tells them what website to go on. They go ahead and take an assessment. The assessment is scored, and then we get all those almost instantly. This web-based system pulls all the information up on a Manpower Plan, it tells us what they’ve applied for, where they’ve worked. Gives us a resume, and then it gives us a score on the assessment.”

The manager continued to explain that once an employee is hired, they enter into a formal training period that is standardized for each occupation. “Training is a huge investment for us and it is constant,” he said. “Training days depend on the position. Bartending training is ten days and servers require eight days. In the kitchen it’s probably about ten days. Every day they write note cards on all their recipes. But they’ll take a final. When they take their final, their test in the kitchen, they have to know every ingredient, every ounce, and every item, for the entire station. That’s why we require them to write note cards.”

Even at higher-end restaurants, employers in the region have built a human resource system that accepts a high rate of turnover. “We try to stay ahead of the game so that we’re always hiring, we’re always interviewing, but hopefully it’s not desperation hires,” says another manager. “And we try to have a mix of needs like people who need fulltime, who can work lunches and brunches and all of that, to servers who really want very part time so that you can kind of over staff on busy shifts and then there’s always someone that wants to go home. There’s always a student that would like a Saturday night off.”

Training in San Francisco is decidedly different. Employers there stress “professional norms,” which translates into efforts to support continuous skill upgrading and quasi-professional development activities that are integrated into the jobs themselves. One employer described that in addition to limited initial training for servers, the restaurant has designed a system to support ongoing knowledge development. “Sometimes we’ll assign different topics like rum to one person and then they come back and they’re responsible for training everyone else, doing kind of an in service just to keep it interesting, keep them motivated to learn,” he explained. “If they’re having to present it to someone else, they’re going to want to know the product. It’s sort of a team approach, you would use the whole team to train the rest of the team. Next week somebody gets vodka, next week somebody gets some small winery up in Napa. And we don’t just do products, sometimes we’ll do a certain vegetable, they have to find out the history of it.”

Another San Francisco employer explained that the opportunity to learn on the job actually becomes a recruiting and retention tool for his staff. “The attraction of working here is that they get to taste a lot of wines,” he says. “It’s a big wine list. They can kind of flex their wine muscles a little bit and be like kind of like mini-sommeliers on the floor. They don’t hand over all the wine sales decisions to me or someone else. They handle it themselves. We’ve had no turnover for two years.”

The upshot? San Francisco employers seem to be seeking out better trained, more experienced workers and expecting more from them, which in turn leads to greater professionalism in San Francisco establishments. Specifically, employers in San Francisco readily describe their ideal employees in language typically used to describe professionals—meaning workers who have recognizable industry-specific skills, typically work full time, and invest in their own training.

The persistence of ethnic and racial divides in the full service restaurant industry

One persistent pattern in full service restaurants that hasn’t changed because of differing labor standards in the two cities is this—employers still view back-of-house workers (line cooks, prep cooks, dishwashers) in a less formal, more racialized frame. Listen to the manager of a corporate chain restaurant in Chapel Hill who also previously managed several independent restaurants in the region:

“The Latino workforce, these guys know how to work. They’ve been typically cooking in their own kitchens for large extended families. This is how they typically grew up. So it’s not like me cooking for a family of four at my house, or a family of five, or even doing a Thanksgiving dinner for maybe nine people. They’re cooking three meals a day or whatever it is, for their extended family or for many people in the household. I think that’s where a lot of those skills come into it just based on how they grew up. Compared to those workers with formal culinary education, I’ve probably kicked more people out of my kitchen who had a formal education, because they think they know everything now. It’s one of those things where if somebody taught you how to cook eggs right, if somebody taught you how to do certain things right then that’s wonderful, but can you actually get in that kitchen and perform and do multi tasks.”

The stated preference for Latino workers as prep cooks and line cooks undermines the utility of formal credentialing programs and codified skills that can be marketed across firms. The connection between ethnic background and perceived work ethic can lead to an assumption that Latino workers are monolithic and interchangeable. This ultimately limits the opportunities for individual workers to move up the pay scale.

In San Francisco, employers also offered a view of back-of-house workers that emphasized ethnic stereotypes rather than formal skills or credentials. Explained one ethnic restaurant manager in the city:

“You know, a line cook position, I hate to say it, most of them are my people, most of them are Mexican. And you know, you try to stay away from anyone who went to serious cooking school, went to a culinary academy, or has an AA in culinary kitchen skills. Mexicans are just a better quality cook, they really are. I hate to say it. They might not know what sous-vide is, but if you teach them once how to braise something, how to do it correctly, they’ll do it better than the guy who went to school. It’s just innate.”

Equating ethnic status with work ethic or “innate” ability may lower barriers to entry for new workers seeking a back-of-house job, yet the way employers frame skill through an ethnic lens reinforces the barrier between front-of-house and back-of-house workers. This barrier is important not only because it limits access to better paid server positions, but also because as labor standards rise wage differential grows. The barriers between back-of-house and front-of-house occupations is an observation that nearly all respondents in San Francisco brought up in response to direct questions about how they reacted to rising minimum wage and other labor standards. In particular, employers claim that higher labor standards exacerbate the difficulty they have in finding and retaining high quality line cooks and prep workers. In their view, since the mandates require them to give raises across the board, including tipped workers whose total hourly income already exceeds the new mandate, they have less financial flexibility to offer higher wages to non-tipped workers.

One of the more interesting way in which employers in the full service restaurant industry in San Francisco are responding to higher labor standards–and the persistent ethnic and racial divide between the back and front of the house–is through radically restructuring compensation practices. Specifically, some employers are eliminating tipping and applying an across the board service charge of 18 or 20 percent in order to redistribute income between front-of-house and back-of-house positions.

The elimination of tips is a relatively rare business model in the U.S. restaurant sector, but there have been a number of recent, high-profile examples that have accelerated the pace of change. The nationally recognized restauranteur Danny Meyer, who owns several upscale restaurants in New York City (Gramercy Tavern, Union Square Café), announced that all of his New York-based restaurants would go “hospitality included” within a year. Meyer told the New York Times that he specifically cited the need to rebalance the pay scale for kitchen staff after the recent increase in minimum wage for restaurant workers in New York.

Some interview respondents in San Francisco gave unprompted support for this compensation model. Said the manager of multiple fine-dining restaurants in the city:

“If I opened a new restaurant of my own tomorrow, I would 100 percent put everybody on salary. I would charge a flat percentage surcharge, and I would, I’d put everybody on salary. Direct-to-customer employees probably start at $65,000 dollars a year and they cap out at $110,000 and non-direct-to-customer employees probably start at $45,000 and also would likely cap out at $110,000. And you know, they would be eligible for raises annually based on performance, and then two bonus structures a year.”

While the ability to raise prices or add significant surcharges in order to eliminate tipping may be limited to higher priced restaurants–or very profitable establishments–it is clear that rising labor standards in cities like San Francisco and New York are accelerating this trend. But one barrier to a more widespread adoption of this approach is the way payroll taxes are assessed. If a service charge is collected by the employer—rather than the employee in the case of tips—and paid to workers in salary or higher hourly wages, then the employer must pay additional payroll taxes into the unemployment system. Two additional interview subjects cited this added cost as a minor barrier to moving to a tip-less model.

What is most interesting about this recent restructuring of compensation practices is not that it will be immediately adopted throughout the industry, but that it illustrates how alternative business models can be possible, including ones that focus on evening the playing field between front-of-house and back-of-house workers. Such employment practices would reduce wage inequality as well as racial and economic inequality.

—T. William Lester is an Assistant Professor in the Department of City and Regional Planning

at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill

Methodology

The methodology employed in the larger research paper (that this issue brief is based on) consists of a set of semi-structured interviews with approximately 15 employers in each case. The interview subjects were restaurant owners, general managers, or other key staff who have direct control or influence over the firm’s human resource strategy. Subjects were solicited from and represent all major restaurant market segments (e.g. family-style, casual fine dining, and fine dining), offering a range of observations according to price point and revenue. Interview subjects were initially solicited via a web-based survey inquiring about the willingness of survey participants to participate in a 45-minute interview. Additional interview subjects were solicited through phone calls and in-person requests by the investigator and a graduate student researcher during business hours. Subjects were compensated with a $50 gift card for participation. All interviews were recorded on digital media and transcribed for subsequent analysis.

Download FileInside-monopsony Download full working paper

This qualitative data collection is used to analyze how employers actively and uniquely construct their labor market practices in the face of institutional constraints such as wage mandates and prevailing industry norms. The interviews go beyond the survey results and seek to ascertain why a reported practice, such as investments in training, were chosen. In addition to the interviews, a web-based survey was conducted between July 1st and August 31st 2014 and collected a total of 104 valid responses. The survey consisted of 15 questions and was intended to gather detailed information on wage levels by occupation, training provided, skill requirements and educational attainment of workers. In addition the survey gathered background information on each restaurant such as market segment, average entrée price level, and number of seats available.