New analysis shows state paid leave programs cushioned the blow of COVID-19, sparking important new questions

Overview

New analysis shows that while Congress was busy debating the parameters of federal paid leave to families dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, state paid leave programs in Rhode Island and California were already at work providing much-needed support to affected workers. Because of longstanding paid family and medical leave programs in these two states, workers were able to access paid leave benefits sooner and for a wider variety of reasons than their peers in states without paid leave social insurance programs.

This column summarizes the key findings from this analysis—an empirically grounded starting place for understanding how workers are accessing paid leave during these public health and economic crises. It continues with a roadmap for researchers, including potential data sources and priority research questions identified by paid leave experts and advocates, interested in examining how state and federal programs supported workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and the recession it caused. Such research has important short- and long-term implications for policymakers developing an equitable, accessible, and permanent federal option for the nation’s paid leave needs.

Paid leave policy in the United States when the COVID-19 pandemic hit

Even before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, addressing conflicts between family and job responsibilities without access to paid family and medical leave was a challenge for U.S. workers. The current public health crisis and related illnesses and school and business closures exacerbate this challenge. While some workers can count on their employers to provide them with paid leave, it is rare: Only 18 percent of private-sector workers have paid family leave and 44 percent have paid personal leave though their jobs. Access to these benefits drops precipitously for lower-income and part-time workers.

Filling these gaps, eight states and the District of Columbia have developed their own paid leave social insurance systems, expanding leave access to most of their states’ private-sector employees. Five of these states—California, New Jersey, Rhode Island, New York, and Washington state—are currently paying out claims, while the remaining states and the District of Columbia will begin paying benefits in 2020–2023.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, these five states had the infrastructure in place to support workers’ time-off needs immediately, while families elsewhere were left to scramble with these new work-life challenges. Then, Congress, recognizing the importance of paid leave during a public health emergency, passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act. Signed into law on March 18 and implemented on April 1, 2020, the new law provides the first federal guarantee to U.S. private-sector workers for paid sick days, which cover a short time away from work to deal with an illness, and paid family leave, which covers longer absences from work to care for a loved one.

This is an historic development for working families, but it is an imperfect solution. The law is temporary, carves out a wide swath of employees who cannot access paid leave, and only offers paid family leave for parents whose regular childcare provider is unavailable. This is a necessary benefit for those parents, but it leaves out many other reasons workers need time off, such as caring for a relative recovering from COVID-19.

While more data on the new federal paid leave system are surely forthcoming, the existing state-level programs offer important immediate insights into how paid leave can support workers during a period of crisis. These state systems were available from the onset of the pandemic and offer workers a wider array of benefits than the federal alternative. How they responded in the early days of the pandemic is an important lesson for policymakers considering a permanent and comprehensive federal paid leave program.

As COVID-19 spread, California and Rhode Island’s paid leave systems responded

A new analysis by the Urban Institute’s Chantel Boyens sheds light on how state systems responded to the increasing need for paid leave as COVID-19 spread. Boyens’ analysis of paid family and medical leave systems in California and Rhode Island, the two states that publicly release timely claims data, shows a sizable increase in new claims following the World Health Organization’s March 11 declaration of a global pandemic. Workers filing these initial claims accessed benefits weeks before the Families First Coronavirus Response Act was implemented.

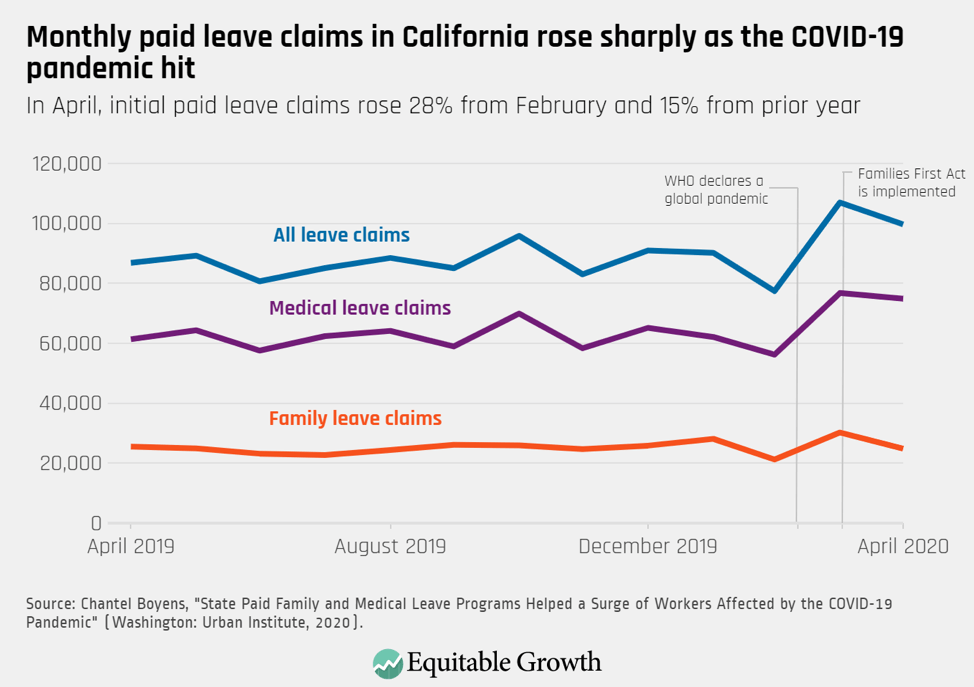

In California, 106,989 new paid family and medical leave claims were filed in March 2020 and 99,695 were filed in April 2020. In March, the first month of the pandemic, claims rose by 29,601—or 38 percent—from the month prior, representing a 16 percent increase from March 2019. The majority of these new claims were for medical leave, but family caregiving claims also exhibited a 43 percent February to March increase and a 13 percent increase from the year prior. By April, medical leave claims remained 22 percent higher than the year prior, but family caregiving claims fell to prepandemic levels. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

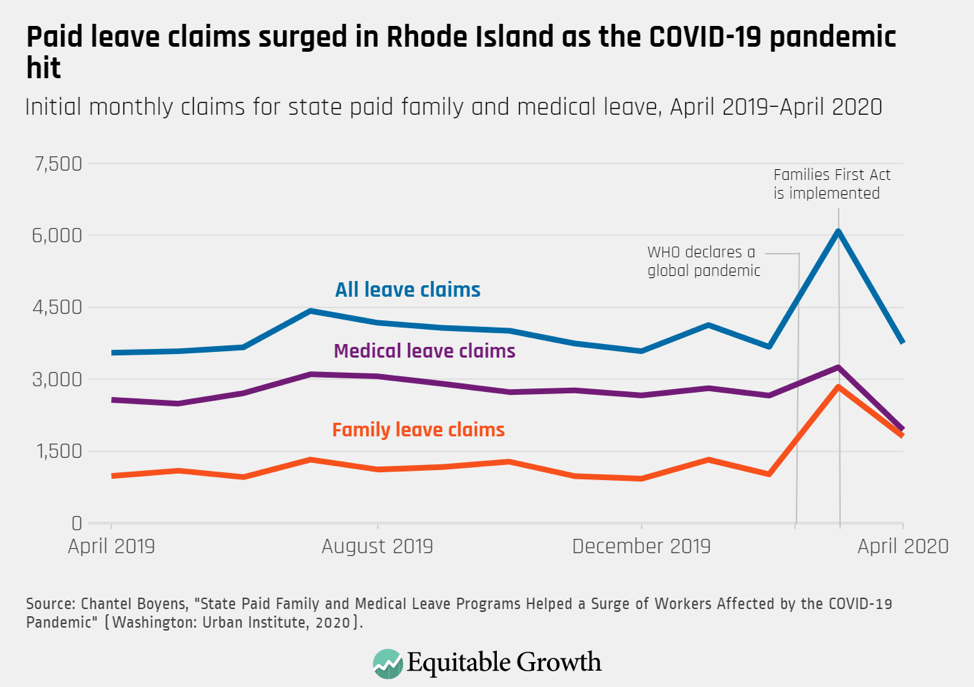

On the other side of the country, data from Rhode Island tell a similar story, with one key difference. According to Boyens’ analysis, new family caregiving claims in Rhode Island nearly tripled from February to March—an increase from 1,016 to 2,841 new claims, or 180 percent. Medical leave claims also rose in March to 3,248 from 2,659, representing a 22 percent bump from the prior month. Claims in April did return to roughly prepandemic levels, though this drop was not uniform across all types of leave. (See Figure 2.) Unlike California, Rhode Island’s decline in claims was largely driven by a fall in medical leave claims, but family caregiving claims remained 84 percent higher than in April 2019.

Figure 2

In Rhode Island, the spread of COVID-19 remained low in the first half of March, but policymakers worked quickly to prepare the state’s paid leave system for the crisis. March 12, 2020, just one day after the WHO declared a pandemic, Governor Gina Raimondo (D) approved executive action that expanded the reasons individuals could quality for leave, waived waiting periods, and loosened medical certification requirements for those with a COVID-19-related illness. This effort to push workers toward the state’s paid leave system appears successful, particularly in the weeks before the federal program was accessible.

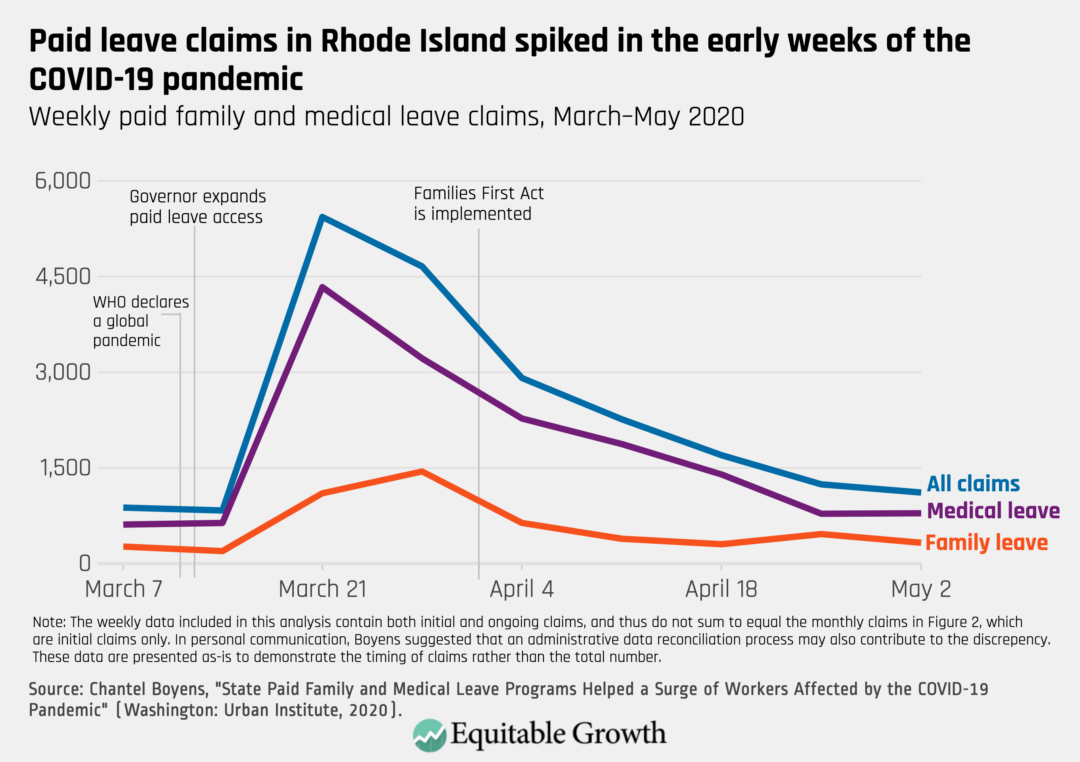

Boyens finds that the largest spike in claims occurred in Rhode Island in the second half of March, following the WHO’s declaration and Gov. Raimondo’s emergency order. The weekly peak of claims for family caregiving leave occurred later than that for medical leave, possibly due to the timing of statewide childcare center closures on March 16 or a lag in the public’s awareness of these benefits. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Rhode Island’s weekly data include initial and continuous claims, so the number of claims presented in the weekly numbers exceeds the monthly data detailed in Figure 2. Still, the pattern in these data is clear: The number of workers requesting new leave or continued time away from work rose dramatically in the early weeks of the pandemic. These workers accessed benefits relatively early in the public health crisis.

Research on paid leave during the pandemic could offer valuable insight during the current public health crisis and beyond

Boyens’ analysis is an early glimpse into how the paid family and medical leave systems in two states responded in the beginning months of what is shaping up to be a protracted public health and economic crisis. More research is needed, however, to understand the accessibility and use of paid leave during this pandemic, not just in California and Rhode Island but also in the other jurisdictions with paid leave programs and the rest of the country accessing paid leave for the first time via the federal Families First Coronavirus Response Act.

In the short term, such research could inform programmatic tweaks to the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and other related programs. The new federal law constructed a paid leave system during a crisis and was unable to benefit from the existing infrastructure and public awareness available in states such as California and Rhode Island. More research on how the program is working in real time will help policymakers and regulators make necessary adjustments. For example, analyses that examine benefit eligibility and access by demographic groups may reveal opportunities for targeted public education. Further, any evidence that paid leave has positive public health implications or health system cost implications may encourage policymakers to expand the benefits offered through the Families First Coronavirus Response Act or extend the program beyond 2020.

In the longer term, research on how access to paid sick leave and paid family and medical leave supported workers during the COVID-19 pandemic will be instructive for policymakers designing a permanent system at the federal level. Already, existing research provides valuable insight into how such a system could be designed. Still, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and ancillary programs are an opportunity to study alternative benefit models and delivery systems and learn from their successes or inefficiencies. Some important research questions include:

- How are state paid leave programs, unpaid leave programs, and the Families First Coronavirus Response Act serving the needs of workers affected by COVID-19? How do these program compare in terms of:

- The demographic and socioeconomic status of people served?

- The eligible population’s awareness of the programs?

- The sizes and characteristics of firms where employees are accessing leave?

- The reasons for taking leave?

- The duration and timing of leave-taking?

- The return-to-work rate after the leave period?

- Barriers to leave-taking?

- Take-up rates?

- The impacts on key outcomes, including health, material hardship, care recipient well-being, COVID-19 diagnoses, public health, hospital admissions, health insurance continuation, and health systems costs?

- How do these paid leave programs compare to other programs that workers may have used for wage replacement when not able to work during the pandemic? Other programs include:

- Unemployment Insurance

- Workers compensation

- Stimulus payments

- Wages covered by businesses that accessed the Paycheck Protection Program

- Wages covered by businesses that did not access the Paycheck Protection Program

- Employer-provided paid time off

- Unpaid time off

- Private charitable contributions

- For workers taking family caregiving leave, which family members are they caring for? How is this impacted by the definition of a “family member” included in the applicable paid leave program?

- How does leave-taking behavior vary by the level of job protection (no job protection, anti-retaliatory protection, full job protection) included in the applicable paid leave program?

- How does leave-taking behavior vary in jurisdictions that mandate employer-provided sick leave? Is paid family and medical leave being used to substitute sick days for workers without this benefit?

- Does paid leave access impact the rate of COVID-19 infections? If so, how?

- How have claims to state leave systems been impacted by the implementation of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act?

- How are workers sequencing benefits during this crisis?

- What is the leave-taking behavior of workers carved out of Families First Coronavirus Response Act? Are they foregoing leave, taking unpaid leave, accessing alternative benefits, using pandemic unemployment benefits, leaving work, or something else entirely?

For researchers interested in these or related questions, some potential data sources include:

- State systems’ administrative data. California and Rhode Island share monthly leave data going back years, and New Jersey produces useful annual reports. Other states may be willing to negotiate data-sharing agreements with researchers.

- The U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, which includes several questions on paid leave use, caregiving needs, and other measures of economic security and well-being during the coronavirus pandemic.

- The COVID Impact Survey, available from the University of Chicago’s National Opinion Research Center, which asks a variety of questions on respondents’ well-being, economic security, food security, physical health, and interactions with one’s community and social network during the coronavirus pandemic.

The Household Pulse Survey allows for the most direct comparison between workers with caregiving or health needs by paid leave access. If the survey continues, researchers may be able to study the impact of states implementing their own paid leave systems in the coming months. The District of Columbia will start paying benefits in July 2020, and Massachusetts will begin in January 2021. The COVID Impact Survey does not include a specific measure for paid leave access, but researchers can leverage variation in paid leave eligibility by state of residence or size of employer to generate intent-to-treat estimates.

Conclusion

Researchers have been studying the impact of paid leave for decades, but the coronavirus recession and the diversity of federal, state, and local responses raises new research questions about workers’ demand for paid family and medical leave and the most effective government response. Continuing to build upon the existing paid leave research base will inform a stronger federal solution that supports families, employers, and the economy during the remainder of this pandemic and beyond.